Winners Poems of 2024 Vivian Shipley PoetryAwards

FIRST PLACE: Laurie Zimmerman

Lunar Eclipse Litany, East and West

My neighbors say my little dog

howled all day while I was gone.

Maybe howling at raccoons back east

where I lived in the country, how they hid

under the lilacs nights and peered out at me.

Or howling here in the west at innumerable cats

creeping the paths of cactus and broken glass.

Howling the memory of a grandchild

knocking daily at my door, planting

her handprints on the window

who was once in love with us but now

thousands of miles away, forgetting.

Howling a sudden rumble when armadas

of snow used to skid from the roof

howling reports of falling palm fronds

hitting the concrete, setting off car alarms

howling the bears snorting loudly in leaves

howling bullets zinging against electric wires

frogs piping from the crust of vernal pools

or rotor-wash beating the iron-barred door.

Howling country, howling city

howling east and west, thrash of grasses

screams of addicts in the alley.

I'm envious of my tiny dog, how she howls

for the catastrophes around her, then lies down

though still trembling, to nap, even now next to me

moaning as if the walnut of her heart

is cracking open, as if hearing my blood

howling too because wildfires, because

tear gas, because lies and children in cages

because my own unreachable babies

howling because the parking lot full of dark

and two more friends dying, another stranger

lynched in the park, because disappearing

coral reefs and cheetahs, because soot

visible in the air, because drought

because rising water and islands of plastic

because cancer, because earthquakes

broken bridges and breached levees

ice on the power lines and piles of snow.

Let's howl instead because dangling pomegranates

because fields of turkeys, a flock of bluebirds

because here or there, in spite of startled, in spite

of sad or tired or frightened or night, because

sometimes hopeful, despite too few bees

bumping the abundance of grace-berried cherries

some hanging, some falling, because sometimes

full moon, though sometimes this eclipse.

Judge’s comments:

Beautifully crafted with musical language and sensory imagery, this litany of howling had me coming back to it again and again. The poem perfectly pivots in the middle from the napping tiny howler, “moaning as if the walnut of her heart / is cracking open,” to the speaker who takes over with their own reasons to howl. A volta occurs four stanzas from the end, ending the poem in gratitude for good things we can all howl at.

SECOND PLACE: Panika Dillon

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Judge’s comments:

This poem’s power lies in vivid imagery, charged with figurative language, beautiful sound, and line breaks that yield tragic surprises. The ending picture of children mortaring themselves into the “seams of soil,” along with the double meaning of “mortared,” is unforgettable.

THIRD PLACE: Lynn Pedersen

After Moving, I Train Myself to Call This Home

The key is to leave the new house as many times as possible in the first hours and days, hitch a ride with a family member going to pick up bread or get gas & each time pay attention to what stores are on each corner, where the school is, the library, the pharmacy, how you’d get there on foot or by bike & never think back to the last city or compare the 1960s ranch to this 1970s split level & which is dumpier or consider how you’ve just gone from an unfenced half acre of Kentucky bluegrass with oaks & a homemade swing to a chain link yard of scrabbly shrubs & grasshoppers & no climbing trees, from a street named for a president to one named for a Union soldier & railroad man & how long it’ll take for friends to contact you, if they ever do—no, comparisons will disorient you & make you sick—so instead, you focus on the snowy peaks of this state’s license plate, count the number of chain restaurants, note how the Rockies are due west & always visible, so no matter where you are, you are not lost as you try to memorize street names, call out the correct left & right turns on the way back & pulling into the driveway you say over & over: this is.

Judge’s comments:

This prose poem offers an engaging, comprehensive set of steps in one long, run-on sentence of concise language and specific details that range from a “1970s split level” to a street named for “a Union soldier & railroad man.” With this breathless training regimen, the poet shows how one can get through and accept a difficult life change.

This poem’s power lies in vivid imagery, charged with figurative language, beautiful sound, and line breaks that yield tragic surprises. The ending picture of children mortaring themselves into the “seams of soil,” along with the double meaning of “mortared,” is unforgettable.

THIRD PLACE: Lynn Pedersen

After Moving, I Train Myself to Call This Home

The key is to leave the new house as many times as possible in the first hours and days, hitch a ride with a family member going to pick up bread or get gas & each time pay attention to what stores are on each corner, where the school is, the library, the pharmacy, how you’d get there on foot or by bike & never think back to the last city or compare the 1960s ranch to this 1970s split level & which is dumpier or consider how you’ve just gone from an unfenced half acre of Kentucky bluegrass with oaks & a homemade swing to a chain link yard of scrabbly shrubs & grasshoppers & no climbing trees, from a street named for a president to one named for a Union soldier & railroad man & how long it’ll take for friends to contact you, if they ever do—no, comparisons will disorient you & make you sick—so instead, you focus on the snowy peaks of this state’s license plate, count the number of chain restaurants, note how the Rockies are due west & always visible, so no matter where you are, you are not lost as you try to memorize street names, call out the correct left & right turns on the way back & pulling into the driveway you say over & over: this is.

Judge’s comments:

This prose poem offers an engaging, comprehensive set of steps in one long, run-on sentence of concise language and specific details that range from a “1970s split level” to a street named for “a Union soldier & railroad man.” With this breathless training regimen, the poet shows how one can get through and accept a difficult life change.

HONORABLE MENTION: Dawn Dupler

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Winners Poems of 2023 Vivian Shipley Poetry Awards

|

FIRST PLACE: Maia Elsner

Exhibition Opening 1. Nude seeks shelter Through grief-glutted air, egrets slip. The naked lips of a cave swallow. 2. Nude is angry at the artist For making her so porous: the catastrophic world bleeds; she blossoms. 3. Nude attempts to grow a thicker skin But even leaves, hooked fish, sever from the spine; slip- disked as winter comes. 4. Nude is full of questions Though mouth is absent as sky is. Lonely mountain cut from scissor wind. 5. Artist tries out abstraction To fend off what cries in corners: war years, inch-sized hearts, fixed railway lines. 6. Nude begins to understand Earthbound, the water washes out goat intestines; the gutter leaks wild. 7. Nude contemplates suicide Leftover fog hangs necking bramble, soft kisses the river promises. 8. Artist tries out surrealism World: sun-blanched. Colon like cartilage connects white bone: flesh undergrowth. 9. Nude is full of questions How fruit bats suck each clump of mulberry & love like a slaughterhouse. 10. Nude confronts the writer There were no egrets, just a crane, warning: behold the gaped river mouth. 11. Nude discovers they are not a nude But the dusk after rain, when jade butterflies pair; flight in thickened air. 12. Nude walks out of the gallery Under petals scaled like fish. A moth licks the spliced magnolia pink. Judge’s comments: This poem intrigued me with its faceted exploration of identity, purpose, and self-determination through the lens of the introspective ruminations of a piece of art on exhibit. The haiku form allowed the poem to pivot, develop, and challenge the reader to contemplate the issues raised, whether considering art or humanity. |

SECOND PLACE: Ellen Zhang

Home / Hospital 汤 (Soup) Our hands grabbling with shopping bags brimming, call goes straight to voicemail, consider nothing of it until we listen to the doctor’s voice, leaving everything unsaid, professional, but anxiety threads through these kitchen tiles. When I start lining the refrigerator with yogurts and jams. 妈妈 says maybe—slicing 绿葱. Her acts of love--it is nothing. Everything is glitched time. The returned calls, aroma of beef noodle 汤, scheduled office visits. These are, my mother calls them, lily pad moments. Should we have remembered more from those pebbled times? When I sunk your fingers into mine, intestines collapsing onto itself, peonies blossoming beneath skin. How heavy are pronouns? Your face, a mirror, rising and falling between sterile blue sheets, distance dissipating in unimaginable ways. Still-closed, wet & watery mornings as I sneak in home-made 汤--it is everything, even now you reassure me. Your fingers trembling across my cheeks, flush juxtaposing ghost. It’s all wrong the way I feel your pain of eons ago, sustain this hurt. Consider the way our bodies meldable, yet intact. Silhouettes. 妈妈, let’s go back, to when we held my body at bay, my cells quieting down between flesh, bone, breathes in our warm kitchen. We celebrated my remission, felt like we were full of spinning stars, releasing prayers. 妈妈, let me tell you, it is everything, I am suspended with wait, Judge’s comments: This poem’s elegance enamored me. Its concise language, expert enjambment, and unexpected imagery guide the reader through a journey of love’s bittersweet struggle to heal human frailty. THIRD PLACE: Kelly Houle

Landscape With A Blasphemy Of Stars Truly, just as the asp stops its ears, so do these philosophers shut their eyes to the light of truth. --Galileo Galilei That night, as in a fresco by Bertini, between two stands of cypress on a hill, my father gestured toward the telescope wheeled out for visitors to view the moon with all its godforsaken seas brought close enough to name. Daughter of Galileo, I took my turn, stepped up to witness the bright and floating world already drifting out of view. Next, the ears of Saturn, Jupiter’s four moons, then Venus, in quarter phase, a proof, he liked to say, that it, too, revolves around the sun. The space inside my lungs grew full and round, but my great aunt, in full-length tunic, veil, and wimple, stood back, refused, as if forbidden by some force to see. Saturnine, she turned, went back inside before the sky turned black enough to reveal that milky band of stars, the glittering arm stretched out across the body of the sky. Judge’s comments: This ekphrastic poem complements its inspiration painting. The shared title establishes a wide shot of the setting. At the same time, the poem captures the coming-of-age moment when a father shares the expansive universe with his daughter, seemingly offering her a place where an older generation of women dared not venture. |

Honorable Mentions

HONORABLE MENTION: Victoria Buitron

Still No Rain

My amygdala is with

the tomatoes that are

now rot in the drought

grass, either way the

storms will come,

we’ll confuse bones

for storm-stripped bark,

nail remnants for anthracite,

erosion for once dog-whelk

tongues—sand will make a

home in the cuticles of my

grey matter, excavate loose

diction, and I’ve made a

womb on the porch,

waiting for a deer to bow--

to shed its crown of antlers,

not a peace offering,

not a gift, not a knife,

but a reminder we can

let bones grow outside

our bodies too.

Still No Rain

My amygdala is with

the tomatoes that are

now rot in the drought

grass, either way the

storms will come,

we’ll confuse bones

for storm-stripped bark,

nail remnants for anthracite,

erosion for once dog-whelk

tongues—sand will make a

home in the cuticles of my

grey matter, excavate loose

diction, and I’ve made a

womb on the porch,

waiting for a deer to bow--

to shed its crown of antlers,

not a peace offering,

not a gift, not a knife,

but a reminder we can

let bones grow outside

our bodies too.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Antoinette Brim-Bell 2023 Contest Judge

Antoinette Brim-Bell (Antoinette Brim), Connecticut’s 8th State Poet Laureate, is the author of three full-length poetry collections: These Women You Gave Me, Icarus in Love, and Psalm of the Sunflower. She is a Cave Canem Foundation Fellow and an alumna of Voices of Our Nations Arts Foundation (VONA). Her poetry has appeared in various journals, magazines, textbooks, and anthologies. Additionally, Brim-Bell has published critical work and essays. A sought-after speaker, editor, educator, and consultant, Brim-Bell is a Professor of English at Capital Community College in Hartford, CT.

2022 Contest Judge Charles Rafferty

Charles Rafferty has published 15 collections of poetry -- most recently A Cluster of Noisy Planets(BOA Editions, 2021). His poems have appeared in The New Yorker, O, Oprah Magazine, Poetry Daily, Verse Daily, The Writer's Almanac With Garrison Keillor, Connecticut River Review, Prairie Schooner,and Ploughshares. His second collection of stories is Somebody Who Knows Somebody (Gold Wake Press, 2021). His stories have appeared in The Southern Review, Milk Candy Review, Juked, Okay Donkey, and New World Writing.His first novel is Moscodelphia (Woodhall Press, 2021). Rafferty has won grants from the National Endowment for the Arts and the Connecticut Commission on Culture and Tourism. Currently, he co-directs the MFA program at Albertus Magnus College and teaches at the Westport Writers’ Workshop.

Vivian Shipley Contest Winners 2022

FIRST PLACE: Srinivas Mandavilli

Blackouts

I played with a swan when bored, turning its long shiny steel throat, revealing the belly and there

lay betel nut leaves, slake lime, clove and cardamom. In its silver eyes there was darkness. The

windows were covered in newspapers painted black, and just before the sirens sounded, I would

run to my neighbor’s house. Rabindra sangeet always seem to play on a spool tape player. I was

shy and seldom ate the okra boiled with rice. In the rising steam, they were always so soft, so

moist, so green. Once I heard my parents talk about the naughty twin brothers from the

neighborhood. They were last seen walking holding hands along train tracks. That week I

grabbed onto a live wire, and remained quiet, unmoved, worrying everyone and a soothsayer was

called to examine my hands. My best friend stopped coming over. Years later found that her

father had passed away, poisoning himself using a rusted metal pin as a toothpick. I am latitudes

away, but still look at where the soothsayer’s finger had rested on each mound of my right palm

following its lines to the wrist. I had not heard what he had told my parents and I retrace those

lines again and again. They stretch across my body, all the way to my head, my feet. Sometimes,

I trip over those lines. I am watching the ticking bright radium hands of a clock and can hear the

mythical golden

bird yoked to horses

studded with pearls and parting

the weltering night

Judge's Comments: This strange poem makes use of the haibun form. It is a remembrance of something far away and long ago. Terrible things have been happening – childhood friends run down by trains, a father poisoned by a rusted metal toothpick, the windows of a home papered over and painted black for reasons we never learn. And yet the poem ends in radiance – with the narrator “watching the ticking bright radium hands of a clock,” and with a haiku that somehow explains, without effort, the density of the preceding paragraph.

Blackouts

I played with a swan when bored, turning its long shiny steel throat, revealing the belly and there

lay betel nut leaves, slake lime, clove and cardamom. In its silver eyes there was darkness. The

windows were covered in newspapers painted black, and just before the sirens sounded, I would

run to my neighbor’s house. Rabindra sangeet always seem to play on a spool tape player. I was

shy and seldom ate the okra boiled with rice. In the rising steam, they were always so soft, so

moist, so green. Once I heard my parents talk about the naughty twin brothers from the

neighborhood. They were last seen walking holding hands along train tracks. That week I

grabbed onto a live wire, and remained quiet, unmoved, worrying everyone and a soothsayer was

called to examine my hands. My best friend stopped coming over. Years later found that her

father had passed away, poisoning himself using a rusted metal pin as a toothpick. I am latitudes

away, but still look at where the soothsayer’s finger had rested on each mound of my right palm

following its lines to the wrist. I had not heard what he had told my parents and I retrace those

lines again and again. They stretch across my body, all the way to my head, my feet. Sometimes,

I trip over those lines. I am watching the ticking bright radium hands of a clock and can hear the

mythical golden

bird yoked to horses

studded with pearls and parting

the weltering night

Judge's Comments: This strange poem makes use of the haibun form. It is a remembrance of something far away and long ago. Terrible things have been happening – childhood friends run down by trains, a father poisoned by a rusted metal toothpick, the windows of a home papered over and painted black for reasons we never learn. And yet the poem ends in radiance – with the narrator “watching the ticking bright radium hands of a clock,” and with a haiku that somehow explains, without effort, the density of the preceding paragraph.

SECOND PLACE: Rosa Lane

Dents de Lion

Scroll to read poem below.

Dents de Lion

Scroll to read poem below.

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Judge's Comments: I like the way this poem focuses on a tiny piece of the world – in this case a dandelion flower gone to seed – and simply gets it right. The observations are surprising despite our familiarity with this plant that many people would like to see eradicated. This poem also gives us the phrase “summer’s hands sweet with dirt.” So there’s that!

THIRD PLACE: Claire Scott

COLD BLEAK LACK VERSUS SPRING CROCUSES

Sweet Pea Journal sent an email accepting my poem

“Cold Bleak Lack,” which I wrote while staring

at six orange vials and a bottle of vodka.

Did you know seventy percent of the universe

is made up of dark energy?

They want me to change “ODing on despair”

to “feeling slightly blue,”

and delete the first five stanzas.

And they want a more upbeat stanza to end the poem,

like “something something something spring crocuses.”

Really? Who cares about crocuses when you are

careening over a cliff, no strawberry bush

to cling to on the way down.

Yes you can take my heart of glass

and toss it on the floor. Ha!

They have no idea about scab-picking the past.

The slow seep of sorrow like a leak in the basement,

unnoticed until you slip-slide in murky memories.

A child wears a wool sweater in summer

to hide swelling bruises.

A girl walks beside a freeway

her backpack filled with favorite books.

Listen: the devil is tuning his fiddle.

Can you hear the recorded laughter

of the long dead?

Can you see the burst of yellow

as crocuses flame the snow?

Judge's Comments: This is a funny poem – mocking the idea that a poem needs to have an upbeat, positive message. In this case, an editor has asked that the poet remove the line “ODing on despair” and end the poem with something about “spring crocuses.” The request is ludicrous, and yet this poem finds a way to satisfy the request, which by the poem’s closure has become a stunning rebuke.

COLD BLEAK LACK VERSUS SPRING CROCUSES

Sweet Pea Journal sent an email accepting my poem

“Cold Bleak Lack,” which I wrote while staring

at six orange vials and a bottle of vodka.

Did you know seventy percent of the universe

is made up of dark energy?

They want me to change “ODing on despair”

to “feeling slightly blue,”

and delete the first five stanzas.

And they want a more upbeat stanza to end the poem,

like “something something something spring crocuses.”

Really? Who cares about crocuses when you are

careening over a cliff, no strawberry bush

to cling to on the way down.

Yes you can take my heart of glass

and toss it on the floor. Ha!

They have no idea about scab-picking the past.

The slow seep of sorrow like a leak in the basement,

unnoticed until you slip-slide in murky memories.

A child wears a wool sweater in summer

to hide swelling bruises.

A girl walks beside a freeway

her backpack filled with favorite books.

Listen: the devil is tuning his fiddle.

Can you hear the recorded laughter

of the long dead?

Can you see the burst of yellow

as crocuses flame the snow?

Judge's Comments: This is a funny poem – mocking the idea that a poem needs to have an upbeat, positive message. In this case, an editor has asked that the poet remove the line “ODing on despair” and end the poem with something about “spring crocuses.” The request is ludicrous, and yet this poem finds a way to satisfy the request, which by the poem’s closure has become a stunning rebuke.

HONORABLE MENTION: Chuck Madansky

Cross Examination

To hear the faint sound of oars in the silence as a rowboat

comes slowly out and then goes back is truly worth

all the years of sorrow that are to come.

--A Brief for the Defense Jack Gilbert

I wonder what you mean by worth--

that we pay

for a sunlit kiss

with a leper’s sore?

or that

torture has meaning

equal to

the shrill taste

of a Fuji apple?

or that

a five-day-old child

dead from sepsis

is somehow less unbearable?

God wants us, you say,

to enjoy our lives, between

and before and despite.

But laughter and slaughter

live together—from that

there’s no relief.

Enjoyment is always

the splash of oars, faint

in a sea of grief.

Judge's Comments: I love a poem that wants to argue – in this case with the epigraph’s proposition that the sound of oars will make up for all your sorrows. While the counter-argument is an easy one to make, the poet is clever in their response (e.g., “laughter and slaughter live together”), and the unexpected rhyme at the very end closes this poem like “the click of Yeats’s closing box.” A perfect ending.

Cross Examination

To hear the faint sound of oars in the silence as a rowboat

comes slowly out and then goes back is truly worth

all the years of sorrow that are to come.

--A Brief for the Defense Jack Gilbert

I wonder what you mean by worth--

that we pay

for a sunlit kiss

with a leper’s sore?

or that

torture has meaning

equal to

the shrill taste

of a Fuji apple?

or that

a five-day-old child

dead from sepsis

is somehow less unbearable?

God wants us, you say,

to enjoy our lives, between

and before and despite.

But laughter and slaughter

live together—from that

there’s no relief.

Enjoyment is always

the splash of oars, faint

in a sea of grief.

Judge's Comments: I love a poem that wants to argue – in this case with the epigraph’s proposition that the sound of oars will make up for all your sorrows. While the counter-argument is an easy one to make, the poet is clever in their response (e.g., “laughter and slaughter live together”), and the unexpected rhyme at the very end closes this poem like “the click of Yeats’s closing box.” A perfect ending.

Vivian Shipley Contest Winners 2021

FIRST PLACE: John Sibley Williams

At This Table We Sing with Joy, with Sorrow

If not for the body, let’s rafter this old table up

like once-believe-in hymns simply for the sake it.

Let’s brush the dust of dead stars from the lacy cloth.

Scrape our plates free of what our grandparents failed

to finish & our children, hopefully, will never learn

to swallow. Every night it seems the worst of us

takes over & again the table sinks out of reach.

The glass always half-empty, and we empty it.

All this amaranth scattered across the floor so we can hear

our ghosts when they enter, & when they leave us. So much

unwilded rice & unprepared longing. How we cannot stop

mending what is not yet broken & killing to prove the world

still needs us. There are still so many unlit fires in our ovens,

sometimes I forget there’s meant to be a difference between us

& them, between an unpainted & a burning cross. My daughters

carry my name like a cross over their tender little shoulders.

I no longer know what to say when asked for the truth.

Whose truth will keep the sorrow from their song?

Someone handcrafted this unvarnished oak so we might

one day take stock of one another. Let’s prop our history up

on piles of unread books, so nothing wobbles, so the legs

grow equally tall, so even that uncle they say struggled

to hurt others the way he would never be hurt can join us,

all the ugliness intact, & his wife who conformed to her container

like goat milk. Let’s sit, please, at this table between my own mixed-

race daughters & the hate you’d have had for them. Here’s some crushed

berries for your toast. A dull knife to spread it. Outside nothing has changed

of the American sycamore apart from what we’ve chosen to hang from it.

Judge’s Comment:

This is a poem that joins the personal and the historical, that uses the traditional image of gathering around the dinner table in a wholly new way: this table that “sinks out of reach” with our failures is the place where our historical hatred is examined, and where the hope keeps rising that somehow, some way the speaker’s mixed race children can both carry and transform the crosses they have been given to bear. It is a poem of fresh language and images that places its speaker both in actual and historical time, at a table that must be continually propped up and raised by our efforts to truly “take stock of one another.”

SECOND PLACE: Matt Hohner

This Poem Has Been Sanitized for Your Protection

This poem is organic, macrobiotic, made with 100% recycled,

post-consumer language, and trigger-free. Surface meanings

have been scrubbed clean with disinfected phrasing. References

to sadness, massacres, mistreatment of people and Mother Nature

have been replaced with images of gentle, fluffy animals doing

cute things with babies. Theme and tone have been thoroughly

vetted by a panel of experts, clergy, and business leaders so as

not to threaten the status quo. Diction and syntax were generated

using renewable energy. All negative thoughts have been converted

to the American Dream. No one will die in this poem. Everyone will

go to heaven. Every word in this poem is a military or professional

sports hero. This poem can be played on any format radio station.

Reading this poem out loud replenishes rainforests and coral reefs.

Its carbon footprint is negative. Whales sing this poem to their young.

Whispering this poem resurrects forgotten tongues and extinct species.

This poem is child-safe; none of its easily recognizable allusions

to western culture contain nuts, wheat, eggs, meat, gluten, sugar,

salt, pesticides, herbicides, or lactose. Your aunt from Des Moines

will ask you for a copy of this poem. Every metaphor is food-safe,

hypoallergenic, anti-microbial, and certified fair-trade. This poem

will never be censored on Facebook. These lines will be used in

speeches by kind and benevolent world leaders because no one can

argue with clean poems. This poem extols beautiful things without

being specific, because safe poems use words like beautiful

and everyone loves them. This poem will look good in a gold

frame on your living room wall. Read this poem at weddings

and funerals. You wish you wrote this poem, and you could have,

because it’s safe, and good, and beautiful, and everyone loves it.

Judge’s comment:

A truly inventive tongue-in-cheek romp about safety-proofing our world, which of course can’t be sanitized or made safe. The poem has a finely tuned ear for the cliches of our time and knows how to turn those cliches on their head and, more seriously, make the reader aware of both what we think we want and what precisely we don’t want—a sanitized world where “all negative thoughts are converted to the American Dream.” And it is a list poem that knows how to make a list function with a beginning, middle and end. And what a wonderful place in which the poem ends up.

THIRD PLACE: Karen Holmberg

As It Should Be

Bleached reeds, shattered by the waves’ delicate

insistence, tallied in lots of two or three,

are as they should be.

The light glazing the low knuckles on a cast

crab shell, turned ruddy as a nipple,

is as it should be.

The scrawl of leaf litter, mahogany brown,

a fine tobacco marking the tide’s

highest grasp, is as it should be.

The brittle monarch tilting this way and that,

scudding an inch or two in puffs

of wind, is as it should be.

The salt tolerant plant, stem torqued and cracked

by footfalls, one leaf still reaching its torn palm

for the sun, is as it should be.

Whether it lives or dies

is as it should be.

They have taken up your minerals,

your elemental particles.

Because you are not

as you should be, your mind

riven by cancer’s gall,

not as it should be.

Not as the whitened leaf

held afloat by the oak gall, sentenced

to an early fall in barely August.

Unless we can say, as the leaf would say,

so be it. Unless we can let you be

like the dying leaf,

replete: another cell

in the world’s endless

unbuilding and rebuilding body.

Judge’s comment:

A passionate and moving poem about accepting the cost of “cancer’s gall”; like Jane Kenyon’s “Let Evening Come,” this poem accepts change and death in the natural world because they are “as it should be,” a refrain that repeats and repeats until it finally and brilliantly changes to “not as it should be,” a line this time in reference to the loved one’s mind which is “riven” by cancer. But then, the poem makes a final and expansive change: can we see the loved one’s body and its cancer cells like the cells of the “world’s endless/unbuilding and building body.”

HONORABLE MENTION: Sarah Key

My Rickrack Trip

Started with a darting a zig-zag

up and down Ninth Street, East Village,

a panic of pandemic shopping for a foray

to my favorite stores. Had they survived

the corona? I landed at Love Only where a navy

polka-dot mask promised to protect me. The clerk said

“$5 more” for the one trimmed in white rickrack.

Worth it for the word alone, rickrack stacked up

like pins along my tongue, and when I bowled them

down, I felt as if I’d stolen shamelessly like Arsène Lupin

or his recent re-embodiment by Omar Sy,

oh, the Netflix binge. Yes, my turn

to be a gentlewoman cabrioleur. I took

that bon-bon of a word, sweetly the wee ric rolled

around my tongue, all that is small en francais,

I sucked like a hard candy in my mouth.

Those clever French braided it into a twisted twin:

ric à rac. Exactly! As that is what it means,

neither more nor less. Never mind, rickrack wraps

my ears in pleasing muffs, takes me back before

my birth before bric-à-brac fell to flea markets

and kitsch, when dresses from feed sacks

were all the rage on the plains, as women turned

the plain rage of poverty into fashion, they trimmed

Gingham Girl flour sacks with rickrack

its flat and finished edge held up to harsh

washings. Look closely at your rickrack

to see the intricate braiding, fine crenellations

of fabric soft enough to give way in the palm,

stiff enough to tickle. The word is a symphony

of apophony, reduplication crinkling like cellophane,

rick-

rack,

rick-

rack.

Judge’s comment:

A playful poem about pandemic shopping that transforms buying a polka dot face mask into a luscious romp on the word “rickrack” and the sounds and sense of words in our mouths and body.

HONORABLE MENTION: Shellie Harwood

(why I did not) Sleep in the Plagued Years

I wanted to wake up stunned by something,

shaken awake by something to wake for.

A bit that was startling,

that bolted me up from the

900 thread count.

A horn I had grown overnight

from my temple.

A new variety of courage blistering my skin,

urging me to run naked into the street

to fight for something I’d squandered,

some tiny shred of freedom I’d neglected to save.

Wanted to wake

to the shock of a strange hand on my breast,

someone’s I’d never heard of,

an “oh my god who are you and

how did you know to put your hand

just there, just like that?”

Or wake with a new untranslated voice

gushing out of me,

like those people who suddenly speak in tongues

or play Bach’s Concerto in A Minor

without a lesson on the strings.

Wanted to wake and remember

some previous life

I’d lived in Kazakhstan

or Yemen

and begin to rock myself backwards and forward,

wet with relief

for living this one in a country humane, where

I will escape artillery.

Unless, of course, someone should burst in, guns ablaze,

while I was sleeping. That would be a careless mistake, I suppose.

I bargain that I will sleep again

only when this world will wake to surprise me

with a simple morning paper

unfolded in my lap,

bleached and blank and horrorless,

newsless and bodyless, silent as an empty shroud.

Something unstained and glorious, something pristine,

something bloodless to wrap the fish for dinner in.

Judge’s comment:

A parable-like poem of wanting to wake to a world that isn’t plagued by violence and inhumanity. The yearning in this poem is to live in a world that is transformed, where we truly come alive, as if we were speaking in tongues, or had become savanta who can play Bach’s “Concerto in A Minor” without a lesson.

HONORABLE MENTION: Rayon Lennon

Love Letter to My New White Ex-Lover

I adore you more than the Klan

Wants to annihilate us. I wear you

Like a bulletproof vest through

Police sirens and cherry-treed

Neighborhoods. You confess

To blind spots while rooting

Out racist thoughts

The way workers purged

Soil after discovering innocent

Homes sitting on a former

Chemical dump. Only you know

Why I hesitate to call

You ultra beautiful. You are

My favorite wine, off-white,

Summer sweet. You share

The bitter fruits of white

Privilege. You call your high

Credit score racist. There’s nothing

Sweeter than the way

You manipulate your 100-year-old

Great granny to cease spewing

Stereotypes. You rattle off Biggie's

“Born to Die” without tripping

Mines of N-words. You signed us up

For therapy after

America looked at us

The wrong way. You hate

Cardi B and worship

Michelle and Tubman.

You love a man in blues

But blast them for shortening

Black lives. You know the birth

To murdered lives of Sandra,

Tamir, Trayvon....Your favorite

Color is midnight seas.

Mother to nature, you live

To rescue betta fish from seedy

Dollar stores. You taught me

How to kill my fear so a spider

Could live.

Judge’s comment:

Who can resist the opening lines: I adore you more than the Klan/wants to annihilate us”? What follows doesn’t let up, mixing dark humor with the serious questions of mixed race relations and being mixed race in an America that has never come face to face with its historical past of racism.

HONORABLE MENTION: Melissa Ann Goodwin

Are You My Mother?

They are already in the circle when I come in.

I spot her right off, tucked between two old ladies –

one looks perplexed, her gaze wandering the room,

the other, lost in another dimension. And Mom,

alert, attentive, like a well-behaved student awaiting

the start of class. Thick white hair, shiny

and nicely brushed. Skin glowing with ironic

good health. Neat blouse, red cardigan

with gold buttons, khaki pants, sturdy

Rockports – at least some things don’t change.

An aide sidles up to me.

That’s my mother. I say her name.

She won’t know me. I just want to see her.

To watch for a while. Please don’t say anything.

It will upset her. (And me).

I sit beside an old nun; she reaches over and takes

my hand. Center stage, a different aide explains

the Plan for the Day. The one I spoke to, not a moment

ago, taps Mom’s shoulder from behind and points.

Loud whisper: That’s your daughter.

I cringe. At the words, the confused look on my mother’s

face, the white-hot pain searing my heart. All eyes on me

now – curious, suspicious. In this alternate dimension,

where long ago is the present, and the present is soon forgotten,

daughters are four-feet tall and eight years old.

When I was small, Mummy read aloud, Are You My Mother?

In which, the baby bird, fallen from the nest, wanders off,

asking this question of everyone it meets. Mom stares at me

intently, brow furrowed. My cheeks burn; pleading eyes ask,

Are you my mother?

She flashes a polite, awkward smile, like one you’d give

someone who accidentally bumped you, to show

there are no hard feelings, shakes her head and says,

just like the animals in the story,

I am not your mother.

I throw murderous eyes at the aide and force

a smile filled with gritted teeth. My voice piercing

the stillness sounds high and hollow:

Don’t mind her. She’s got it wrong.

Mercifully, someone asks, What’s for lunch?

The grace of short memory spans –

they all lose interest in me, and fast.

Shepherd’s Pie, the aide says.

Someone: What’s that?

The aide’s mouth opens, but

Mom’s voice is already in the air:

You don’t know what Shepherd’s Pie is?

I choke back a laugh. Now that sounds

like my mother.

Let me tell her!

And then, my mother, who does not know

that it’s fall, or that we’ve sold the house, or

that Daddy is just across the way in long-term care,

or that she once sailed down the Nile past

the Valley of the Kings, who does not know

that she is the mother of the gray-haired

woman sitting beside the nun, explains,

in a clear and dearly familiar voice,

and in exquisite detail, how to make

a Shepherd’s Pie.

Judge’s comment:

A moving poem that brings together the popular children’s book with a mother’s dementia. This a poem that makes its meaning dramatically, as a visit to the speaker’s mother in a care facility becomes a controlling metaphor for an examination of the speaker’s and mother’s identity both as individuals and as mother/daughter.

HONORABLE MENTION: Kathleen McClung

Deep Cleaning

Confess. I’m derelict in certain ways:

I do not floss each day. Nor do I write.

Oh sure, my journal brims: complaints, checklists

of bills to pay. But stanzas hide somewhere

most days, resisting will. I wait them out,

rejoice when, shy or bold, they sing. But back

to teeth. My last clinic cleaning? Months back--

before a virus trampled us in ways

no one imagined. No one ventured out.

No hair salons. Who dared perform the rite

of manicure, bikini wax, pierced ear?

Clandestine services by specialists,

true, got arranged. Few dental hygienists

risked house calls, though. Millions like me lapsed. Plaque

steamrolled: incisors, molars, everywhere.

Perhaps the traffic eased on roads, freeways,

but in our mouths, gum lines clogged up. Why write

of teeth, you ask? Why not an ode about

eyelashes, lips? (More lyrical no doubt.)

Last week’s appointment topped my To Do list.

I’d made the call in June. The time seemed right

to reunite with Rick—my first time back.

Fourth floor, great view, the bridge not far away.

I’d missed the ritual, not quite aware

how much. Behind the gear he had to wear--

the mask, shield, gloves—his goofy wit leaked out:

“Forgive me waterboarding you. Our ways

of torture haven’t changed.” He sped through lists

of musicals he loved (they all went back

a dozen years or more), scraped left, then right,

methodical, and though he would be right

to reprimand my flosslessness, nowhere

did Rick pronounce my flaws. Just said “Come back”

and pulled a toothbrush from a drawer without

rebuke. A long-stemmed rose. I read the lists

of cases in each state. It’s far away,

pandemic end. Nowhere has it snuffed out.

I write these stanzas, lists of syllables,

small ways I can give back, my tongue on teeth.

Judge’s comment:

A witty Covid sestina about getting one’s teeth cleaned and the attempt to return to some normalcy amid a pandemic that seemingly will not end. A really fine-tuned, smart formal poem.

At This Table We Sing with Joy, with Sorrow

- for Sean Sherman, Oglala Lakota Sioux chef and cookbook author

If not for the body, let’s rafter this old table up

like once-believe-in hymns simply for the sake it.

Let’s brush the dust of dead stars from the lacy cloth.

Scrape our plates free of what our grandparents failed

to finish & our children, hopefully, will never learn

to swallow. Every night it seems the worst of us

takes over & again the table sinks out of reach.

The glass always half-empty, and we empty it.

All this amaranth scattered across the floor so we can hear

our ghosts when they enter, & when they leave us. So much

unwilded rice & unprepared longing. How we cannot stop

mending what is not yet broken & killing to prove the world

still needs us. There are still so many unlit fires in our ovens,

sometimes I forget there’s meant to be a difference between us

& them, between an unpainted & a burning cross. My daughters

carry my name like a cross over their tender little shoulders.

I no longer know what to say when asked for the truth.

Whose truth will keep the sorrow from their song?

Someone handcrafted this unvarnished oak so we might

one day take stock of one another. Let’s prop our history up

on piles of unread books, so nothing wobbles, so the legs

grow equally tall, so even that uncle they say struggled

to hurt others the way he would never be hurt can join us,

all the ugliness intact, & his wife who conformed to her container

like goat milk. Let’s sit, please, at this table between my own mixed-

race daughters & the hate you’d have had for them. Here’s some crushed

berries for your toast. A dull knife to spread it. Outside nothing has changed

of the American sycamore apart from what we’ve chosen to hang from it.

Judge’s Comment:

This is a poem that joins the personal and the historical, that uses the traditional image of gathering around the dinner table in a wholly new way: this table that “sinks out of reach” with our failures is the place where our historical hatred is examined, and where the hope keeps rising that somehow, some way the speaker’s mixed race children can both carry and transform the crosses they have been given to bear. It is a poem of fresh language and images that places its speaker both in actual and historical time, at a table that must be continually propped up and raised by our efforts to truly “take stock of one another.”

SECOND PLACE: Matt Hohner

This Poem Has Been Sanitized for Your Protection

This poem is organic, macrobiotic, made with 100% recycled,

post-consumer language, and trigger-free. Surface meanings

have been scrubbed clean with disinfected phrasing. References

to sadness, massacres, mistreatment of people and Mother Nature

have been replaced with images of gentle, fluffy animals doing

cute things with babies. Theme and tone have been thoroughly

vetted by a panel of experts, clergy, and business leaders so as

not to threaten the status quo. Diction and syntax were generated

using renewable energy. All negative thoughts have been converted

to the American Dream. No one will die in this poem. Everyone will

go to heaven. Every word in this poem is a military or professional

sports hero. This poem can be played on any format radio station.

Reading this poem out loud replenishes rainforests and coral reefs.

Its carbon footprint is negative. Whales sing this poem to their young.

Whispering this poem resurrects forgotten tongues and extinct species.

This poem is child-safe; none of its easily recognizable allusions

to western culture contain nuts, wheat, eggs, meat, gluten, sugar,

salt, pesticides, herbicides, or lactose. Your aunt from Des Moines

will ask you for a copy of this poem. Every metaphor is food-safe,

hypoallergenic, anti-microbial, and certified fair-trade. This poem

will never be censored on Facebook. These lines will be used in

speeches by kind and benevolent world leaders because no one can

argue with clean poems. This poem extols beautiful things without

being specific, because safe poems use words like beautiful

and everyone loves them. This poem will look good in a gold

frame on your living room wall. Read this poem at weddings

and funerals. You wish you wrote this poem, and you could have,

because it’s safe, and good, and beautiful, and everyone loves it.

Judge’s comment:

A truly inventive tongue-in-cheek romp about safety-proofing our world, which of course can’t be sanitized or made safe. The poem has a finely tuned ear for the cliches of our time and knows how to turn those cliches on their head and, more seriously, make the reader aware of both what we think we want and what precisely we don’t want—a sanitized world where “all negative thoughts are converted to the American Dream.” And it is a list poem that knows how to make a list function with a beginning, middle and end. And what a wonderful place in which the poem ends up.

THIRD PLACE: Karen Holmberg

As It Should Be

Bleached reeds, shattered by the waves’ delicate

insistence, tallied in lots of two or three,

are as they should be.

The light glazing the low knuckles on a cast

crab shell, turned ruddy as a nipple,

is as it should be.

The scrawl of leaf litter, mahogany brown,

a fine tobacco marking the tide’s

highest grasp, is as it should be.

The brittle monarch tilting this way and that,

scudding an inch or two in puffs

of wind, is as it should be.

The salt tolerant plant, stem torqued and cracked

by footfalls, one leaf still reaching its torn palm

for the sun, is as it should be.

Whether it lives or dies

is as it should be.

They have taken up your minerals,

your elemental particles.

Because you are not

as you should be, your mind

riven by cancer’s gall,

not as it should be.

Not as the whitened leaf

held afloat by the oak gall, sentenced

to an early fall in barely August.

Unless we can say, as the leaf would say,

so be it. Unless we can let you be

like the dying leaf,

replete: another cell

in the world’s endless

unbuilding and rebuilding body.

Judge’s comment:

A passionate and moving poem about accepting the cost of “cancer’s gall”; like Jane Kenyon’s “Let Evening Come,” this poem accepts change and death in the natural world because they are “as it should be,” a refrain that repeats and repeats until it finally and brilliantly changes to “not as it should be,” a line this time in reference to the loved one’s mind which is “riven” by cancer. But then, the poem makes a final and expansive change: can we see the loved one’s body and its cancer cells like the cells of the “world’s endless/unbuilding and building body.”

HONORABLE MENTION: Sarah Key

My Rickrack Trip

Started with a darting a zig-zag

up and down Ninth Street, East Village,

a panic of pandemic shopping for a foray

to my favorite stores. Had they survived

the corona? I landed at Love Only where a navy

polka-dot mask promised to protect me. The clerk said

“$5 more” for the one trimmed in white rickrack.

Worth it for the word alone, rickrack stacked up

like pins along my tongue, and when I bowled them

down, I felt as if I’d stolen shamelessly like Arsène Lupin

or his recent re-embodiment by Omar Sy,

oh, the Netflix binge. Yes, my turn

to be a gentlewoman cabrioleur. I took

that bon-bon of a word, sweetly the wee ric rolled

around my tongue, all that is small en francais,

I sucked like a hard candy in my mouth.

Those clever French braided it into a twisted twin:

ric à rac. Exactly! As that is what it means,

neither more nor less. Never mind, rickrack wraps

my ears in pleasing muffs, takes me back before

my birth before bric-à-brac fell to flea markets

and kitsch, when dresses from feed sacks

were all the rage on the plains, as women turned

the plain rage of poverty into fashion, they trimmed

Gingham Girl flour sacks with rickrack

its flat and finished edge held up to harsh

washings. Look closely at your rickrack

to see the intricate braiding, fine crenellations

of fabric soft enough to give way in the palm,

stiff enough to tickle. The word is a symphony

of apophony, reduplication crinkling like cellophane,

rick-

rack,

rick-

rack.

Judge’s comment:

A playful poem about pandemic shopping that transforms buying a polka dot face mask into a luscious romp on the word “rickrack” and the sounds and sense of words in our mouths and body.

HONORABLE MENTION: Shellie Harwood

(why I did not) Sleep in the Plagued Years

I wanted to wake up stunned by something,

shaken awake by something to wake for.

A bit that was startling,

that bolted me up from the

900 thread count.

A horn I had grown overnight

from my temple.

A new variety of courage blistering my skin,

urging me to run naked into the street

to fight for something I’d squandered,

some tiny shred of freedom I’d neglected to save.

Wanted to wake

to the shock of a strange hand on my breast,

someone’s I’d never heard of,

an “oh my god who are you and

how did you know to put your hand

just there, just like that?”

Or wake with a new untranslated voice

gushing out of me,

like those people who suddenly speak in tongues

or play Bach’s Concerto in A Minor

without a lesson on the strings.

Wanted to wake and remember

some previous life

I’d lived in Kazakhstan

or Yemen

and begin to rock myself backwards and forward,

wet with relief

for living this one in a country humane, where

I will escape artillery.

Unless, of course, someone should burst in, guns ablaze,

while I was sleeping. That would be a careless mistake, I suppose.

I bargain that I will sleep again

only when this world will wake to surprise me

with a simple morning paper

unfolded in my lap,

bleached and blank and horrorless,

newsless and bodyless, silent as an empty shroud.

Something unstained and glorious, something pristine,

something bloodless to wrap the fish for dinner in.

Judge’s comment:

A parable-like poem of wanting to wake to a world that isn’t plagued by violence and inhumanity. The yearning in this poem is to live in a world that is transformed, where we truly come alive, as if we were speaking in tongues, or had become savanta who can play Bach’s “Concerto in A Minor” without a lesson.

HONORABLE MENTION: Rayon Lennon

Love Letter to My New White Ex-Lover

I adore you more than the Klan

Wants to annihilate us. I wear you

Like a bulletproof vest through

Police sirens and cherry-treed

Neighborhoods. You confess

To blind spots while rooting

Out racist thoughts

The way workers purged

Soil after discovering innocent

Homes sitting on a former

Chemical dump. Only you know

Why I hesitate to call

You ultra beautiful. You are

My favorite wine, off-white,

Summer sweet. You share

The bitter fruits of white

Privilege. You call your high

Credit score racist. There’s nothing

Sweeter than the way

You manipulate your 100-year-old

Great granny to cease spewing

Stereotypes. You rattle off Biggie's

“Born to Die” without tripping

Mines of N-words. You signed us up

For therapy after

America looked at us

The wrong way. You hate

Cardi B and worship

Michelle and Tubman.

You love a man in blues

But blast them for shortening

Black lives. You know the birth

To murdered lives of Sandra,

Tamir, Trayvon....Your favorite

Color is midnight seas.

Mother to nature, you live

To rescue betta fish from seedy

Dollar stores. You taught me

How to kill my fear so a spider

Could live.

Judge’s comment:

Who can resist the opening lines: I adore you more than the Klan/wants to annihilate us”? What follows doesn’t let up, mixing dark humor with the serious questions of mixed race relations and being mixed race in an America that has never come face to face with its historical past of racism.

HONORABLE MENTION: Melissa Ann Goodwin

Are You My Mother?

They are already in the circle when I come in.

I spot her right off, tucked between two old ladies –

one looks perplexed, her gaze wandering the room,

the other, lost in another dimension. And Mom,

alert, attentive, like a well-behaved student awaiting

the start of class. Thick white hair, shiny

and nicely brushed. Skin glowing with ironic

good health. Neat blouse, red cardigan

with gold buttons, khaki pants, sturdy

Rockports – at least some things don’t change.

An aide sidles up to me.

That’s my mother. I say her name.

She won’t know me. I just want to see her.

To watch for a while. Please don’t say anything.

It will upset her. (And me).

I sit beside an old nun; she reaches over and takes

my hand. Center stage, a different aide explains

the Plan for the Day. The one I spoke to, not a moment

ago, taps Mom’s shoulder from behind and points.

Loud whisper: That’s your daughter.

I cringe. At the words, the confused look on my mother’s

face, the white-hot pain searing my heart. All eyes on me

now – curious, suspicious. In this alternate dimension,

where long ago is the present, and the present is soon forgotten,

daughters are four-feet tall and eight years old.

When I was small, Mummy read aloud, Are You My Mother?

In which, the baby bird, fallen from the nest, wanders off,

asking this question of everyone it meets. Mom stares at me

intently, brow furrowed. My cheeks burn; pleading eyes ask,

Are you my mother?

She flashes a polite, awkward smile, like one you’d give

someone who accidentally bumped you, to show

there are no hard feelings, shakes her head and says,

just like the animals in the story,

I am not your mother.

I throw murderous eyes at the aide and force

a smile filled with gritted teeth. My voice piercing

the stillness sounds high and hollow:

Don’t mind her. She’s got it wrong.

Mercifully, someone asks, What’s for lunch?

The grace of short memory spans –

they all lose interest in me, and fast.

Shepherd’s Pie, the aide says.

Someone: What’s that?

The aide’s mouth opens, but

Mom’s voice is already in the air:

You don’t know what Shepherd’s Pie is?

I choke back a laugh. Now that sounds

like my mother.

Let me tell her!

And then, my mother, who does not know

that it’s fall, or that we’ve sold the house, or

that Daddy is just across the way in long-term care,

or that she once sailed down the Nile past

the Valley of the Kings, who does not know

that she is the mother of the gray-haired

woman sitting beside the nun, explains,

in a clear and dearly familiar voice,

and in exquisite detail, how to make

a Shepherd’s Pie.

Judge’s comment:

A moving poem that brings together the popular children’s book with a mother’s dementia. This a poem that makes its meaning dramatically, as a visit to the speaker’s mother in a care facility becomes a controlling metaphor for an examination of the speaker’s and mother’s identity both as individuals and as mother/daughter.

HONORABLE MENTION: Kathleen McClung

Deep Cleaning

Confess. I’m derelict in certain ways:

I do not floss each day. Nor do I write.

Oh sure, my journal brims: complaints, checklists

of bills to pay. But stanzas hide somewhere

most days, resisting will. I wait them out,

rejoice when, shy or bold, they sing. But back

to teeth. My last clinic cleaning? Months back--

before a virus trampled us in ways

no one imagined. No one ventured out.

No hair salons. Who dared perform the rite

of manicure, bikini wax, pierced ear?

Clandestine services by specialists,

true, got arranged. Few dental hygienists

risked house calls, though. Millions like me lapsed. Plaque

steamrolled: incisors, molars, everywhere.

Perhaps the traffic eased on roads, freeways,

but in our mouths, gum lines clogged up. Why write

of teeth, you ask? Why not an ode about

eyelashes, lips? (More lyrical no doubt.)

Last week’s appointment topped my To Do list.

I’d made the call in June. The time seemed right

to reunite with Rick—my first time back.

Fourth floor, great view, the bridge not far away.

I’d missed the ritual, not quite aware

how much. Behind the gear he had to wear--

the mask, shield, gloves—his goofy wit leaked out:

“Forgive me waterboarding you. Our ways

of torture haven’t changed.” He sped through lists

of musicals he loved (they all went back

a dozen years or more), scraped left, then right,

methodical, and though he would be right

to reprimand my flosslessness, nowhere

did Rick pronounce my flaws. Just said “Come back”

and pulled a toothbrush from a drawer without

rebuke. A long-stemmed rose. I read the lists

of cases in each state. It’s far away,

pandemic end. Nowhere has it snuffed out.

I write these stanzas, lists of syllables,

small ways I can give back, my tongue on teeth.

Judge’s comment:

A witty Covid sestina about getting one’s teeth cleaned and the attempt to return to some normalcy amid a pandemic that seemingly will not end. A really fine-tuned, smart formal poem.

|

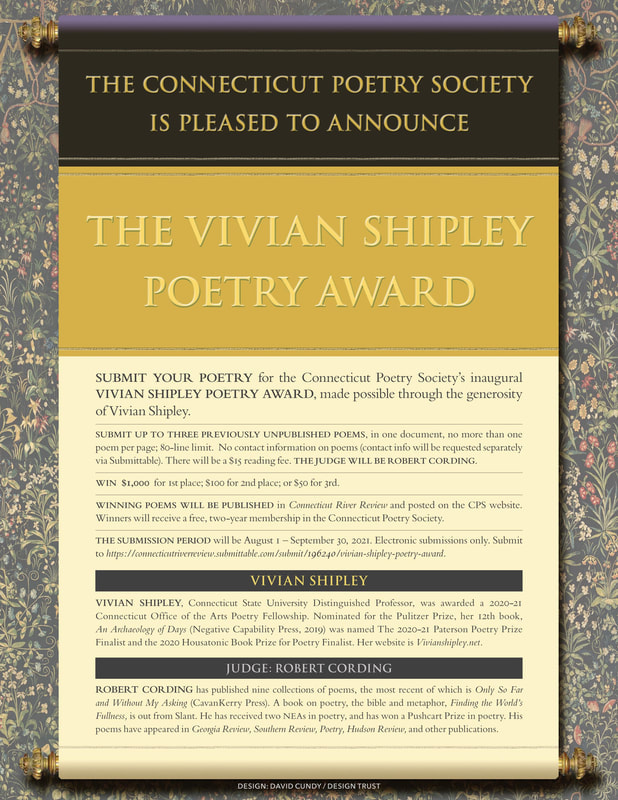

The Vivian Shipley Poetry Award Prizes: $1000 –1st place; $100 – 2nd place; $50 – 3rd place Winning poems will be published in Connecticut River Review and posted on the CPS website. Winners will receive a free, two-year membership in the Connecticut Poetry Society. Submission period has ended for this year. Contest Policy

We accept Electronic entries only via Submittable. Judges are asked to select first, second, and third prize winners, and to provide a very brief blurb on the winning entries (commenting on what made them stand out). At his or her discretion, one-three honorable mentions may also be selected. First, second, and third prize winners of the CRR Contest and the Connecticut Poetry Award contest will be published in the Connecticut River Review journal. Winners of a CPS-sponsored contest are not eligible to win an award the year following the year after being selected as an award-winner. CPS board members are not eligible to enter CPS-sponsored poetry contests. |

This contest is made possible through the generosity of Vivian Shipley. | ||||||