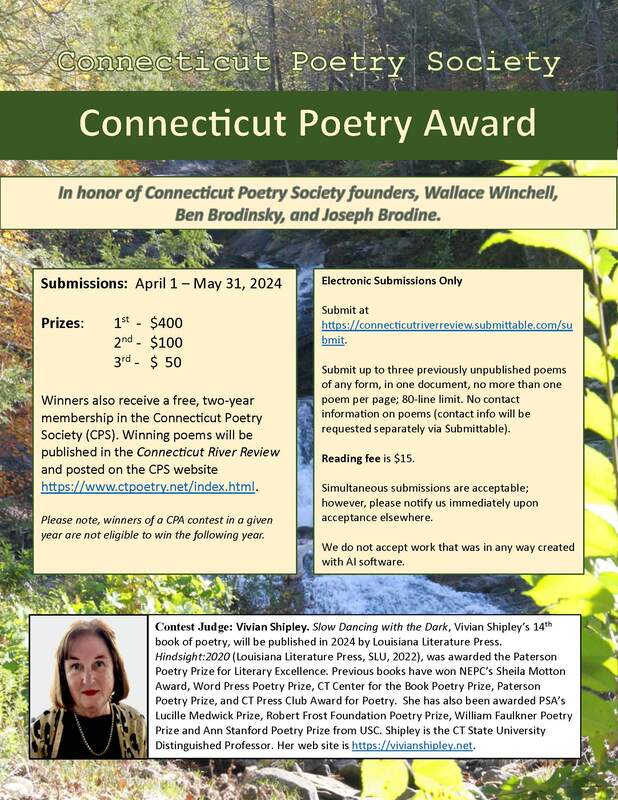

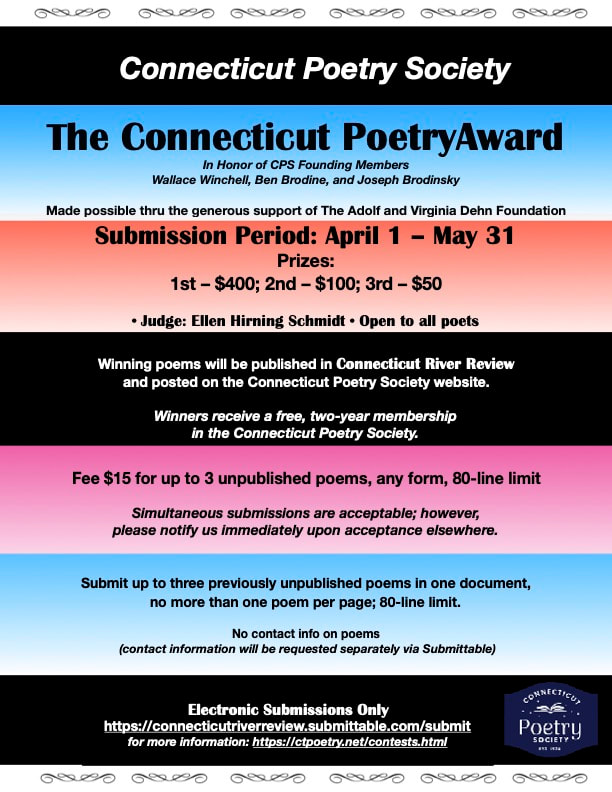

Connecticut Poetry Award

CONNECTICUT POETRY AWARD CONTEST

In Honor of CPS Founding Members

Wallace Winchell, Ben Brodine, and Joseph Brodinsky

Made possible through the generous support of

The Adolf and Virginia Dehn Foundation

Submission Period April 1 – May 31

Open to All Poets

Prizes: 1st $400; 2nd $100; 3rd $50

Click Here to Submit

In Honor of CPS Founding Members

Wallace Winchell, Ben Brodine, and Joseph Brodinsky

Made possible through the generous support of

The Adolf and Virginia Dehn Foundation

Submission Period April 1 – May 31

Open to All Poets

Prizes: 1st $400; 2nd $100; 3rd $50

Click Here to Submit

Ellen Hirning Schmidt to Judge 2025 Connecticut Poetry Award Contest

Award- winning poet Ellen Hirning Schmidt first submitted poems for publication when she turned 70 in 2017. She received the Helen Kay Poetry Chapbook Prize for Oh, say did you know, as well as a Pushcart nomination, a Connecticut Poetry Society Award, and was a 2023 American Writers Review finalist. Armed to the Teeth is her first full-length collection (Antrim 2023). Retired from a crisis center, Schmidt designed and teaches Writing Through the Rough Spots, online workshops for students from the United States and 15 countries. She leads summer workshops on Star Island, NH.. www.WritingRoomWorkshops.com

Winners of the 2024 Connecticut Award

FIRST PLACE: Arlene DeMaris

Telling the Hive

Knock first to get their attention. Call them out of their city,

away from their industry of pollen and wax. Break the news

gently, inserting the name of your dead. Say what you’ve rehearsed

about the comfort of ceremony, the soul waiting just offstage

and angels wandering in, taking their places on the ceiling.

But in fact you are here to multiply your grief by the number

of wings that will carry it. To make a relic of sweetness.

To say, each absconding is new whenever it happens.

And the ones behind it, the line so long it disappears.

Tell the hive this is not the worst that can happen, but it is

the last. Tell what you disbelieved that morning until the fog

cleared and you saw its bare branches. Tell what the earth

was doing to itself that day, the hills greening up, covered

in starlings pulling the pale wet bodies of slugs from the soil.

Judge’s remarks:

When Queen Elizabeth II died, the royal beekeeper attached black bows on the hives before informing the bees that their queen was dead. Curious about how the poem would utilize this tradition, the first line “Knock first to get their attention” immediately pulled me into “Telling the Hive” and I continued to be impressed every time I returned to Arlene DeMaris’ masterful poem which is actually a very complex exploration of death, the ultimate human mystery, and that in fact, DeMaris depicts the difficulty we all face in dealing with death when it occurs to others and also how confronting it personally by telling the hive is a way to multiply grief “by the number of wings that will carry it.”. Trying to make a “relic of sweetness” the speaker tells the hive “it is not the worst that can happen” but adds “but it is the last.” The final graphic image of starlings “pulling the pale wet bodies of slugs from the soil” conveys an unvarnished message about the constant presence of death hovering over us all.

SECOND PLACE: Shellie Harwood

Little Boy in Gaza

In my nightgown still,

fleece robe drawn tight against me

from the first fall morning’s chill.

I let you pour my coffee, swirling with white cream,

into the worn red mug,

let my fingers wrap like a lover’s around it,

pull it close against my cheek.

Old trees trail their aching fingers

across the window panes, beckoning,

but I am drunk with the luxury of peace.

You kiss the top of my head, child that I am,

and we stand together as always in this season of departure,

rapt in the explosion of autumn’s topaz, flame and sweet burnt umber.

You click the remote, quite absently,

in that casual way we usher in the morning headlines,

jolted back from splendor to the harsh and reckless day.

And I hear the man say,

There is a little boy in Gaza,

taken without his glasses.

It weighs on his father to think of Ohad lost in a dark place.

He cannot manage. His father says it twice.

Ohad cannot manage.

He will quake from war he cannot see.

A blast of leaves rain heavy down, explode outside our window,

forming colored craters in the yellowing yard.

I feel the coffee spill, watch it splatter

across the ivory robe that has fallen open,

that no longer warms me.

And I think of the terrible noise to come

of dead stars falling, of bodies falling across and behind the border,

bombs and mortar shells,

the fall of each tiny lens

beneath the crush of frantic feet.

And little matters now,

but that Ohad is lost in dark without his glasses.

I close my eyes, I hear you close your eyes behind me.

Little boy,

better not to see.

Judge’s remarks:

I was drawn to “Little Boy in Gaza” at once because it captures the struggle I and many of us have each day to reconcile our lives of ease “drunk with the luxury of peace” with the constant media coverage of obliterating wars and the deaths that multiply day by day that threaten to numb and desensitize us. Writing a poem about a child or a political poem presents a challenge and Shellie Harwood manages to accept and overcome the inherent difficulty of the subjects She succeeds in writing about both a political struggle and a boy by focusing on one child, Ohad, a child in Gaza, making him unique by adding the masterful detail that he was “taken without his glasses” by soldiers. Harwood contrasts the “bombs and mortar shells” with “the fall of each tiny lens.” We are left with the picture of Ohad “lost in dark without his glasses” as Harwood addresses him and perhaps us in the conclusion to the poem: “Little boy, better not to see.”

THIRD PLACE: Lauren Crawford

What I Have in Common with a Shovelhead Shark

We're on the bay boat thirty miles deep into the Gulf of Mexico. I've got a shark

that's too big for my pole on the line. It takes forty-five minutes to reel it in.

When the line gets too rough, step-Sir takes over and gives my arms a break.

This is a fight with a creature we don't yet know. But somehow, Sir knows.

Before the long, amber tail flicks a little too close to the surface, before that

pointed nose thrashes through the water, he somehow knows what I've got.

My arms ache, my sun-stained forehead sweats, and I'm out of breath trying

to rip my prize from its home, from everything it knows. Soon enough though,

the fight is over, we win, and all five massive feet of the shark is in the boat with us,

razor teeth slashing, that wicked tail wreaking havoc, knocking lures, bobbers

and apple slivers overboard. I back away, not knowing what to do, but Sir

rushes forward and begins bashing that shovelhead with his fist right between the eyes.

I have to knock him out, he says, or he'll hurt someone when we try to handle him.

Bang goes Sir's fist; bang, bang, bang. It takes a while, the shark is strong,

but for once, I am grateful for his violence. For once, its function is truly protection.

Each blow slows the shark's stuttering movements until his knuckles begin to bleed.

For once, we all agree it's necessary and I can't stop looking at those dorsal veins popping,

the swift, elegant force of his swings. How brutally beautiful it must be to kill a king.

When it's over, Sir's hand is wrecked. Out of water, their skin is like sandpaper,

he tells me, feel him. And I do. I run my hands along my catch, down that long, golden

body leaking the Gulf from his gills. In my mind I try to piece together where I belong,

how I am meant to live but all I can hear is that stiff, hollow sound, that bang

rattling the boat like a signal, like I'm simply waiting for something to end.

Judge’s remarks:

The specific and unflinching detail of “What I Have in Common with a Shovelhead Shark” stayed with me on multiple reads. Lauren Crawford creates a speaker who is very aware of what she is doing in “trying to rip my prize from its home, from everything it knows.” The bestial nature of the shark with “razor teeth slashing, that wicked tail wreaking havoc,” is not a surprise, but the brutality of Sir, the captain, is startling as he bashes the shovelhead between the eyes with his fist until his knuckles bleed and the shark’s dorsal veins pop. The speaker runs her hands down the shark as if it is a lover with its “long, golden body leaking the Gulf from his gills.” Raising the questions inherent in the killing of another species for the sport of it, the speaker ponders “where I belong, how I am meant to live” but offers no rationale or excuse for the fish’s death. She leaves the reader wondering about the title and if it is the brutality, the bestiality that the fish and the speaker have in common.

Judge’s remarks:

John Paul Caponigro’s “Everyone In Your Dream Is You” feels dreamlike in its illogical logic and fanciful style. “If you fall from a great height, catch yourself,” which is only possible in dreamland. Or “eternity is a blink, a blink is eternity.” Or “You are the egg and the egg layer.” The reader is constantly off balance, rather like dreamers who wake with a jolt, feeling as if they are falling, relieved to discover they are not. Pondering these imponderables, the reader notices that certain words have been crossed out. “Watch some body your body caught in waves.” This attention getting device is directly related to a constant struggle the individual faces trying to preserve a unique identity in the face of the constant bombardment from influencers in the social media: “One self is always drowning in another self.” The reader is pulled into the struggle to maintain the self by reading the lines both ways, both with the words lined out and not, which also adds to the otherworldly feeling of the poem. Finally, even the title suggests a double reading: “Everyone in Your Dream is You.” Does this mean the reader, the writer, or both? John Paul Caponigro has created an intriguing poem that invites multiple readings and will stay with the reader long after the page is put down.

Honorable Mention: Deborrah Corr

Night Vision

On our backs in the grass my sister

aimed her flashlight upward as if

its feeble beam could penetrate the night

and teach me to trace the constellations.

Stories in the sky. How the Greeks

or their gods hurled their enemies or allies

against the black expanse. And still they hung

for me to find the outlines of their transformation.

I pretended I could see, could believe what she

told me, just to keep her there, keep her

speaking into the dark. If I lay now in that yard,

long ago plowed under, where would I find

the form of my sister? There’s no weight to hold

her indentation on a lawn made of memory.

When my daughter died, her friends told their son

she was now a star in the heavens. Look up.

You’ll see her shining. Their boy, at three, had sat

on her hospital bed and read to her–

was it Cat in the Hat or Go Dog Go? At the end

of each page, he looked up and aimed his dimpled

smile at her, the joy of the words she’d taught him

sparkling on his teeth. And she, by-passing pain,

gleamed a grin back at him. I search the night sky.

I am overwhelmed by glowing mass. So pointless

to think I could ever find her. The stars answer back

with more stars, the poet tells me. My sister’s

flashlight can’t create her shape. The truth is,

I don’t believe it. Nor did my daughter.

When I asked, in her last days, what she

thought was coming, her answer was quick:

nothing it’s the end lights out. Truth is,

I wanted an answer from the other side.

Truth is, I wanted to be left a spark.

I want her life, shortened though it was,

to be narrated every night by points of light.

Once, alone, on that long ago lawn,

I stared up as twilight dimmed the sky. It was

the color of the lilacs that breathed their scent

into the cooling air. Night, a thick liquid,

flowed down the curves of the inverted bowl above me.

My eyes scanned the arc, waiting for what I knew

would appear–the first freckle of a star, so dim

I almost believed I’d made it up, but when

I looked away and back again, there it was

shining brighter. Then they all rushed in,

blinking on as if they couldn’t wait to be awake

and watching the world. Now it was all

blackness, spread with fields of gold.

That was the time I believed in a god and the stars

of his creation. I believed in the invisible.

How too much daylight can keep you from seeing.

I called my sister two days before she died,

checking in about her heart. She was up

and cleaning. I told her she should be in bed.

Let someone else do the chores. She’d been

talking with God, she said. That was all

the help she needed. I failed to call again.

I had failed her so many times before. I know

She could never quite forgive me, when,

As a newly-formed adult, I dropped the faith.

But we choreographed a careful dance

around the tender, burnt flesh of that topic.

It left us untouchable.

410 light years from earth, seven sisters cluster

inside Taurus, the bull. A safe place Zeus made for girls

pursued by a hunter. My sister’s God was never so protective.

Last April we lit a candle to celebrate

my daughter’s fiftieth–a decade of years

she never got to count. In Spring, Virgo returns–

Persephone reunited with Demeter, the mother

who laid the earth barren to get her child back.

How powerless I am.

My daughter, when she was five, lay beside me

on a blanket. As night slipped in, with its first faint stars,

she said it was like they were squeezed from a tube.

She reached out and plucked one,

and placed it on her tongue.

Note: the poem contains a quote from

Victoria Chang’s “Starlight, 1962”

in With My Back to the World

Judge’s remarks:

The difficulty in writing a lengthy poem is uniting the various strands and, of course, keeping the reader’s interest. Deborah Corr does a masterful job of both in “Night Vision.” She pulls the reader into the poem by depicting her and her sister on their backs identifying constellations of stars which inserts Greek myths of gods who hurled them into the sky. The subjects of stars, her sister and Greek myth are then woven into the poem’s tapestry. The reader immediately learns that her sister is dead, saying “There’s no weight to hold her indentation on a lawn made of memory.” The death of the speaker’s daughter is immediately introduced and the astrological relationship is created by a friend who offered consolation saying “she was now a star in the heavens.” The speaker cannot find either her sister or her daughter, revealing what she wants is “to be left a spark.” Continuing to search the night sky, she again threads in Greek myth with the “seven sisters cluster inside Taurus, the bull. A safe place Zeus made for girls.” In spring, she thinks of Virgo then of Persephone reunited with Demeter” a mother who got her child back concluding, “How powerless I am.” Ultimately, the only way to find consolation the speaker offers herself and the reader is to return to memory: her daughter at five who pretends to reach out and place a star on her tongue.

Honorable Mention: Kathryn Jordan

Solitary Bee

Three days in the house of my old father.

He sits, hunched over, thumbing pages of

a piece written to honor him, determined

to point out mistakes. I offer an apology.

He says, Are you sorry for what you did

or that you wrote it? Then, You know what

I think. I take the bait: “Why isn’t this over?”

My father is silent, still scrolling my work.

I go to my room, consider the cost to fly

home today. Through a dark glass, I see

a bee hovering at the open window, which

I rush to close to a crack, lest a bug enter

or—God forbid—a wild, fresh prairie wind.

The bee lands near a hole in the lock, starts

to dig, tiny legs tugging at tiny bits of web

and shit, squeezing its body into an opening

scarcely larger than itself, emerging to kick

away traces of clinging clotted matter. She

flies off, returning to clear the space inside

over and over. Does she never tire of this?

The sun goes down behind still-bare trees,

washing the prairie of light. All is hushed

and calm, though I don’t know what changed.

I crouch by the window, peering out, hoping

she can rest, solitary bee, hidden in her cave.

Judge’s remarks:

In“Solitary Bee,” Kathryn Jordan utilizes I.A. Richards’ concept of vehicle and tenor in her poem by artfully utilizing a bee’s activity to explore the real subject of the poem which is the speaker’s troubled relationship with her father. What is so significant is the way in which the speaker conveys her sorrow without sinking into sentiment. In doing so, she touches a universal problem of the only too common continuing struggle between children and parents which is frequently not resolved before or after death. The speaker has come seeking her father’s love, his approval by sharing a lengthy tribute. Rather than react with gratitude, he proceeds to “points out mistakes.” Falling into an old pattern, she apologizes. Going even further, he critiques her pages and brings up past sins: “Are you sorry for what you did?” Fleeing back to her room, the speaker shows her disappointment by contemplating the cost of flying home early. Offering a glimpse into her childhood where opening a window risked letting in a bug or fresh air, she sees a bee, who like the speaker returns over and over to a small hole in the window trying to carve out space. The speaker must be referring to herself when she asks, “Does she never tire of this?” Offering some solution for her own struggle, she hopes the bee “can rest, solitary bee, hidden in her cave.”

Winners Connecticut Poetry Award 2023

FIRST PLACE: Kaecey McCormick

Bruin Walk

On Bruin Walk at the edge of UCLA’s campus

a squirrel, fat from stolen bagels and chips, dropped

from the gnarled branches of an oak to the pavement.

It twitched and twitched as blood pooled beneath

its tiny skull and we all, rushing to the dorms or with

friends to eat or on our way to meet a lover, stopped--

pulled by the gravity of the tiny being’s last moments

on earth. We inhaled and watched, the way years before

we stood side by side in a classroom, watching a space shuttle

explode; the way, a few years from then, we’d watch as first one

and then another plane turned skyscrapers to dust; the way in middle

age we’d watch a mob break our capital. We were all watching--

the basketball players, the loners, the math geeks, the art

students, the fraternity brothers already buzzing. We couldn’t

look away. We could feel a life leaking out, lifting us out

of ourselves for a moment, joined in a collective sigh until

one girl, long, braid swinging, drew closer than the rest.

She approached the squirrel slowly, hands out, and kneeled

by it, stroking its soft sides, looking at it the way you,

no matter your years or your religious beliefs, hope Death’s

angel looks at you, like you were the prodigal returning

home at last, like you were the first star against the dark.

All of us gathered there, even the birds above and the rats

moving through the bushes, stilled, each of us becoming

for a moment the squirrel—comforted by a steady hand

on our body, a welcoming gaze on our trembling eyes,

soft words of assurance in our ear as we paused, then

exhaled our last breath.

Judge’s remarks:

The author evokes a busy outdoor space, then stops time for a campus crowd as a thoughtful young woman extends a hand to comfort a dying animal. Skillful changes in scale hold the reader’s interest from everyday life to bloody death, from global news to local particulars. These quatrains move with deliberate grace.

SECOND PLACE: Laura Rodley

Perfume of Childhood

Hay dry and crackly under sneakered feet,

crunch of dried stalks and tang of crushed clover,

bite of creosote on railroad ties,

the burnt grass besides the rails

after new creosote has been applied,

sulfur in the air just before a thunderstorm,

metallic smell from sun-baked outside faucet

at a friend’s house as you washed your hands,

cupped water up to your face and drank it,

the dank stink of skunk cabbage broken

as you crossed the stream by the short wooden bridge

that was caved in, uncrossable, yet

you crossed the creek, made it home in time.

Cotton candy, the cloying sweetness,

you so rarely ate it, mesmerized by the spin,

its gathering wool on the paper cone,

the cigarette haze lingering on the server;

holding paint upside down, squirting it on the card

that spun on the wheel, the paint oily,

the resulting painting blaring but beautiful,

sun hot on your hair and your new sneakers,

the shoveled dung of the pony that sat

on its haunches at the Arden Fair.

I do not remember being born there,

but I remember the dark rush of the creek water,

the mallard ducklings that paddled their feet

with no fear of snapping turtles,

only the crisp coolness cast

by the shade of the hemlocks overhead,

encircling The Green in greenness,

its everlasting swift scent sharp,

the spongy-red yew berries that dripped clear sap

that were poisonous, never-to-eat,

but we tasted the sap just the same.

How did we ever make it out alive?

Judge’s remarks:

The author evokes childhood adventures in a breathless list poem emphasizing smell, with lines like “the dank stink of skunk cabbage broken.” A sharp collage moves toward an edge of danger that enhances the list, “the spongy-red yew berries that dripped clear sap.”

THIRD PLACE: Diane Hueter

Stranger at the Door

He knows I want to read this letter, I need it like water, like salt, like bread.

He offers it up to me, crumpled from his pocket, unstamped, addressed in ink

with only my name in the script I’ve seen so often on grocery lists and birthday

cards, incredibly precise, finely legible, upright letters familiar as fingers.

The stranger has a face as pale as oatmeal, a suit as dark as oil. He assures me

my father promised me this letter when he called last year, when I watched

my gray phone buzz and buzz, dancing over the tablecloth’s map of memory,

until finally my father spoke to the electronic cellar. Months and moons went by,

went from warm to cold, cold to warm, large as a plate, small as a smile. Left me

counting my pulse in the throbbing thumb I cut slicing melons. Left me

holding my years like bags of candy. Is this man a messenger? Is that

his calling? What does it matter now? My father has died. I can’t see

the moon because I broke my teacup, I can't read the tides because I'm lost

in a wheat field, I can’t hold the paper because my fingers are covered in gilt.

Judge’s remarks:

Before email, people wrote to family members and friends. With this missive, delivered in person, the poet plays with handwriting, “upright letters familiar as fingers,” on an unstamped letter that “Left me/holding my years like bags of candy.”

Bruin Walk

On Bruin Walk at the edge of UCLA’s campus

a squirrel, fat from stolen bagels and chips, dropped

from the gnarled branches of an oak to the pavement.

It twitched and twitched as blood pooled beneath

its tiny skull and we all, rushing to the dorms or with

friends to eat or on our way to meet a lover, stopped--

pulled by the gravity of the tiny being’s last moments

on earth. We inhaled and watched, the way years before

we stood side by side in a classroom, watching a space shuttle

explode; the way, a few years from then, we’d watch as first one

and then another plane turned skyscrapers to dust; the way in middle

age we’d watch a mob break our capital. We were all watching--

the basketball players, the loners, the math geeks, the art

students, the fraternity brothers already buzzing. We couldn’t

look away. We could feel a life leaking out, lifting us out

of ourselves for a moment, joined in a collective sigh until

one girl, long, braid swinging, drew closer than the rest.

She approached the squirrel slowly, hands out, and kneeled

by it, stroking its soft sides, looking at it the way you,

no matter your years or your religious beliefs, hope Death’s

angel looks at you, like you were the prodigal returning

home at last, like you were the first star against the dark.

All of us gathered there, even the birds above and the rats

moving through the bushes, stilled, each of us becoming

for a moment the squirrel—comforted by a steady hand

on our body, a welcoming gaze on our trembling eyes,

soft words of assurance in our ear as we paused, then

exhaled our last breath.

Judge’s remarks:

The author evokes a busy outdoor space, then stops time for a campus crowd as a thoughtful young woman extends a hand to comfort a dying animal. Skillful changes in scale hold the reader’s interest from everyday life to bloody death, from global news to local particulars. These quatrains move with deliberate grace.

SECOND PLACE: Laura Rodley

Perfume of Childhood

Hay dry and crackly under sneakered feet,

crunch of dried stalks and tang of crushed clover,

bite of creosote on railroad ties,

the burnt grass besides the rails

after new creosote has been applied,

sulfur in the air just before a thunderstorm,

metallic smell from sun-baked outside faucet

at a friend’s house as you washed your hands,

cupped water up to your face and drank it,

the dank stink of skunk cabbage broken

as you crossed the stream by the short wooden bridge

that was caved in, uncrossable, yet

you crossed the creek, made it home in time.

Cotton candy, the cloying sweetness,

you so rarely ate it, mesmerized by the spin,

its gathering wool on the paper cone,

the cigarette haze lingering on the server;

holding paint upside down, squirting it on the card

that spun on the wheel, the paint oily,

the resulting painting blaring but beautiful,

sun hot on your hair and your new sneakers,

the shoveled dung of the pony that sat

on its haunches at the Arden Fair.

I do not remember being born there,

but I remember the dark rush of the creek water,

the mallard ducklings that paddled their feet

with no fear of snapping turtles,

only the crisp coolness cast

by the shade of the hemlocks overhead,

encircling The Green in greenness,

its everlasting swift scent sharp,

the spongy-red yew berries that dripped clear sap

that were poisonous, never-to-eat,

but we tasted the sap just the same.

How did we ever make it out alive?

Judge’s remarks:

The author evokes childhood adventures in a breathless list poem emphasizing smell, with lines like “the dank stink of skunk cabbage broken.” A sharp collage moves toward an edge of danger that enhances the list, “the spongy-red yew berries that dripped clear sap.”

THIRD PLACE: Diane Hueter

Stranger at the Door

He knows I want to read this letter, I need it like water, like salt, like bread.

He offers it up to me, crumpled from his pocket, unstamped, addressed in ink

with only my name in the script I’ve seen so often on grocery lists and birthday

cards, incredibly precise, finely legible, upright letters familiar as fingers.

The stranger has a face as pale as oatmeal, a suit as dark as oil. He assures me

my father promised me this letter when he called last year, when I watched

my gray phone buzz and buzz, dancing over the tablecloth’s map of memory,

until finally my father spoke to the electronic cellar. Months and moons went by,

went from warm to cold, cold to warm, large as a plate, small as a smile. Left me

counting my pulse in the throbbing thumb I cut slicing melons. Left me

holding my years like bags of candy. Is this man a messenger? Is that

his calling? What does it matter now? My father has died. I can’t see

the moon because I broke my teacup, I can't read the tides because I'm lost

in a wheat field, I can’t hold the paper because my fingers are covered in gilt.

Judge’s remarks:

Before email, people wrote to family members and friends. With this missive, delivered in person, the poet plays with handwriting, “upright letters familiar as fingers,” on an unstamped letter that “Left me/holding my years like bags of candy.”

To submit poems, after April 1 go to

connecticutriverreview.submittable.com/submit

connecticutriverreview.submittable.com/submit