2020 CONNECTICUT RIVER REVIEW CONTEST WINNERS

2020 CONNECTICUT RIVER REVIEW POETRY CONTEST

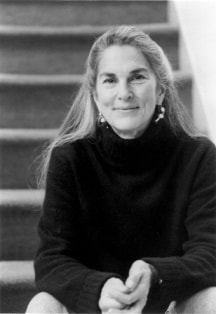

JUDGE, MARGARET GIBSON Judge’s Note: Throughout my reading of the poems sent to the contest, I looked for poems that were grounded in the poet’s local or everyday experience of nature AND which were also able to make leaps and linkages to history or to science, to the social world or to the sacred. The following poems do just that, each with its own striking and credible voice and vision. MG |

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Winners and winning poems 2019, 2018 and 2017 CT River Review Contest Scroll Down

|

FIRST PLACE: Kathleen O’Toole

Sierra Lament

And Peter said, let us erect three tents here on the mountain... Mt: 17:4

I.

Again, a shrine of elements is taking shape

on the sideboard: a scarlet columbine’s Fibonacci

of petals and spurs pokes from a lodge pole cone;

wolf lichen on a bleached bone of juniper--

`

fresh-cut redwood joists

a construction crew breaks

for lunch

The naturalist’s phrases reprise like pillow talk

until, with incense cedar and sagebrush, pungent willow

and heated pine sap, they thread my dreams:

the fruiting bodies of mushroom hypha fusing in the mycorrhiza

first up:

a mountain chickadee

II.

Intoxication accompanies desire

in the realtor’s brochure:

“mountain elegance:

vaulted ceilings, great rooms

could be yours” ...on short sale

Observe and learn about your neighbor. If a mountain lion comes into town,

don’t panic. If you’re watching him, he’s just watching you.

Green-leaf manzanita trades the plenitude

of this season’s fruit to store root energy for the next.

Each species must solve the riddle.

white spruce saplings twist

toward the sun

III.

Some architect’s eye angled these cedar-timbered temples,

in among the A-frames, each wall of windows

more spectacular than the last

What must the Washoe have felt descending

from Donner each summer into such abundance:

harvesting bilberries, fish runs plentiful as aspen;

their horses may have foaled where the golf course

has overrun the old trails....

IV.

How to measure this imposition

of appetite against

remnant tundra under the soil

waiting for the next Ice Age

eight-fingered lupine the raceme’s inflorescence

the advanced cultural memory of ravens ...

August aspen

two Steller’s jays

ward off the crows

JUDGE’s COMMENT:

“Sierra Lament”

“Sierra Lament” demonstrates how a persuasive intelligence and a passionate mind can employ sensitivity to language, a storehouse of acquired knowledge, and the skill of poetic craft to make a poem of remarkable unity and clarity. The poem is constructed around a pattern of contrasts that begins right away with the title and epigraph: lament, offset by moments of transfiguration

so glorious that one wants to memorialize that moment. To memorialize the moment, this poet constructs a shrine on the sideboard of natural objects: a combination of scarlet columbine flowers and a lodge pole pinecone. As she salvages and memorializes beauty from the natural world, outside there is a construction crew that is building with recently sawn redwood. Respect and awe, the poet’s responses to natural beauty, contrast with the appetite to take and use unsparingly. The poem continues to show us a clash of creativities—the architect’s eye that makes an A-frame into a spectacular secular temple is contrasted with the imagined response of the Washoe, an indigenous people who did not set themselves apart from nature but lived at home within its strictures. Using striking and salient examples, the poem reveals that natural world is not separate from the sacred. It has its own intelligence and patience, its strategies for survival. By implied contrast in the final stanza, humans do not. The final image—two Stellar jays warding off crows—gives us a subtle warning. Keep away from what threatens your nest. Preservation is a form of natural creativity and continuation. This poem is a balanced, subtle argument that is grounded and quietly passionate. I applaud what it says and how it says it.

SECOND PLACE: Christie Max Williams

Rock Me Mama

i.

O Mama, rock me.

Rock me in the arms of your sex,

your birth, your wild plenty.

Rock me your full moon in May,

rock me horseshoe crabs by the millions

on the beaches of Delaware Bay,

let me see the moonlight on their ancient armour

as they pave the beach like countless cobbles,

as the great she-crabs pull trains

of he-crabs coupled to their engines

in urgent readiness to spawn the eggs

she’ll lay by thousands in the wet dark sand.

Rock me the break of day

when blizzards of shorebirds shift and juke as one

in crazy flight above the crabs,

sing me their names –

red knots, plovers, sanderlings, and turnstones –

sing the epic journey that brings them

from Tierra del Fuego bound for Arctic nesting grounds,

sing hunger, sing exhaustion, as they descend

upon the bowls of crab eggs on the beach,

gorging themselves on the glistening fecundity,

then rising into flight with peeping cries,

as they’ve done for a thousand thousand full moons in May!

O Mama, can it last?

Can crabs and birds endure

The rising sea, the shrinking shore?

We owe you a tender cooling, Mama –

we owe you a cooling.

ii.

Rock me, Mama.

Rock me in the lap of your tidal sway,

your ebb and surge, your procreant surge.

Rock me a long Alaskan summer day

when salmon schooling by the millions –

Chinook, Coho, Sockeye, Pink –

surge from the sea where the years

have grown them into mighty swimming muscles

flexing with fertility,

surging to shore in search of natal waters,

every brook, stream, and river

a salmon birthplace and destiny

where they will spawn and die.

Rock me the secret salmon compass

pointing unfailingly to home,

as the silent silver salmon

fly swiftly through the water,

then break the surface into air-born flight,

slicing the horizon in flexing flight,

a salmon exultation of grace, fertility, and fate,

as they have done for a thousand thousand summers!

Ah Mama, can it last?

Will the salmon’s compass point through warmer waters?

Will shrinking glaciers feed their natal streams?

A tender cooling, Mama –

You are owed a cooling.

iii.

O rock me, rock me, Mama.

Rock me with your cooing call,

your lullaby of screech and howl,

your deep deep quiet.

Rock me a starry sky in early March,

rock me silence of the frozen banks

along the Platte River in Nebraska,

let me peer through darkness

at the starlit river, the wide slow Platte,

its silent shallow current skimming over ancient mud,

as the horizon silvers with approaching dawn.

Let me almost see the slender silhouettes,

let me in the sky’s faint first pink

see ten thousand silhouettes

of sandhill cranes standing in the shallows,

and let me hear a soft first chortle

as a lone crane rises into wide-winged flight,

as suddenly a thousand cranes rise as one,

and a thousand more, ten thousand more,

lifting into flight against the pinkening sky,

their collective wings a sudden woosh,

their collective chortle a mighty cry

as the sky becomes a cloud of cranes,

tens of thousands wheeling a wide wild circle,

crying a deafening cry of crane-ness,

as they have cried for a thousand thousand dawns in March.

Dear Mama, can it last?

Will the Platte’s wide shallows dry to silt?

Will the cranes find haven here before

they leave to nest in Arctic Canada?

O Mama, a cooling, a tender cooling.

JUDGE’s COMMENT:

“Rock Me, Mama”

This poem thinks large—how do we address the earth during a time of global climate crisis? One way is to let one’s lyric passion “rock on” in a poem addressed to our earth Mama. This compelling poem is a celebration of the earth’s procreant surge—and what threatens that recurring dance of creation. Horseshoe crabs come ashore on a full moon night in May to spawn; shorebirds, who also need to survive, arrive the next day to eat many of those eggs. Creation and destruction balance each other in dance that is ages old. But what about rising seas, shrinking shores, the speaker asks. The warning note has been sounded. Throughout this poem, the heat of passion tips into an awareness of our earth overheated by (implied) human disregard of natural cycles. The salmon are still surging—will they, after the glaciers melt? The poem’s refrain is telling: Mama, you are owed a cooling. The final section focuses a frozen landscape along the Platte River, a starlit river. On the banks at dawn, sandhill cranes, a thousand of them, “rise as one.” This stirring image of unity and whoosh and chortle wrings from the speaker an impassioned cry: “Dear Mama, can it last?” The third and final recurrence of the refrain reminds: we need a cooling—a cooling that is “tender.” Rock and roll procreation and cacophony this poem has aplenty. It also lifts up the value of tenderness—the lover’s awareness of what the beloved needs. A tenderness towards existence. I salute the thoughtful spiritedness of this poetic outcry.

THIRD PLACE: Mark Caskie

Natural History

Forget the baleen, and its throat too narrow

to shove a fist through, its slick swell of back

festooned with sucker fish, barnacles,

streamers of seaweed hooked in the crook

of fins, its gentle nuzzles against the ship,

its plaintive, subsonic wail to its brothers--

believe the old tales of its merciless pursuit

of clippers, crashing through quiet hulls,

its angry eyes rimmed with red vengeance,

its love of human flesh, its greedy maw

swallowing you whole as you slide

down the soft, pink chute into its belly,

cluttered with the wreckage of history--

explorers’ maps frayed and creased,

broken bifocals, a twisted bird cage,

a blue-and-gold epauletted uniform still

upright in a captain’s chifforobe,

the old galley table with its lamp,

the rusted harpoon pierced into its gut

half-floating in the swill at your feet--

recognize these things as yours,

you belong in this place, among your

broken artifacts, the spend days of

the voyage you captained. You would

cage twenty-five miles of birds, and

boil the flesh of whales to perfume

your bloodied fingers—go ahead, refine

the oil for your lamps, light the lantern,

it is better to see where you came from.

JUDGE’S COMMENT:

“Natural History”

The classroom for this history lesson is the belly of a whale, and this poet knows her whales and the history of whaling. The poem takes its reader right into the belly of the beast. Never mind, the poem instructs, the whale’s actual physical characteristics and behavior, its gentleness, its poignant ability to communicate with its kind: for the moment believe the tales of the whale as a killer, be swallowed whole into its belly. The poem asks us to acknowledge the difference between the actual whale and the whale of our fearful imagining. Who can help but think of Moby Dick or of Jonah as the poem asks us to enter the history of our relationship with the mammal we call whale. When swallowed into the whale, and when there is therefore no separation between the whale and the human, we see the contents in the whale’s stomach—the residue of the whaling life: our history of conquest and appetite. The tone of the poem moves from the opening imperative mood, through image and demonstration, to an accusatory chiding. In the belly of the whale, by lantern light powered by whale oil, you can “see where you came from.” This poem convinces by shifting the ground of our perception and understanding. “Natural History” makes us see into the dark of our own nature and go there. Do you get it yet? this poem implies. The poem asks for light of different sort: the light of the understanding required to make change. When perception changes, everything changes. I applaud the careful choice of detail and the convincing voice that guides us through the poem.

HONORABLE MENTION: Jonathan Andrew Pêrez

THE CALL THAT WHIPS THE NIGHT

Anti-Literacy: (n.) 1740, Missouri, A law prohibited whites teaching black america to read or write

A groundskeeper of the golf course heard the pliant song

and made for the pepper plants, made sure they were safe.

The same groundskeeper heard a wintry-sound that sent shivers down the ivy

and rubbed the extending last first-generation irises on the back nine.

The song continued, upon hill tops and throughout the cacophony of police cars;

it bargained with the barrage of change, it reminded

the farms that the forest came first

it targeted everything black, brown, coffee-colored and replete with nutrients

and it sang to the ends of the golf course, where laid bare

the reparations that stole houses, families, wealth, and oral histories

from the dismal swamp

JUDGE’S COMMENT:

“The Call that Whips the Night”

This poem imagines as its microcosmic focus a golf course and a groundskeeper, who may (given the poem’s epigraph) be a person of color. The poem lets the reader know what the groundskeeper hears in this natural and social environment: birdsong becomes outcry. The boundaries between natural and social blur and gradually give way. The groundskeeper hears a “pliant song,” then a “wintry sound” that shivers the ivy and is not drowned out by the noise of police cars. The song continues through changes that imperil, reminding that “the forest came first.” The colors of the earth are various hues of brown and black—the fertile soil is a nutrient. Combined with the epigraph, the poem’s final lines signal pillage, the need for reparation, the theft of indigenous peoples’ wealth and culture, their banishment by a world that privileges what is white. Quietly this poem sounds out the link between environmental and social injustice. It is a wake-up call, “this pliant song” that changes shape throughout the poem, making surprising linkages. Not so surprising, however, when one is able to acknowledge that racial discrimination and the subduing of those who are “other” is not so distant from fear and the need to subdue that underlies the human domination of the earth. A groundskeeper works for someone who has more privilege than he or she. This particular keeper of the ground is one who keeps to the earth and its diversity, able to do what a good poet does—listen well, make connections and linkages, and by creating an imaginary world, allow us to see the world we actually live in. This poem proceeds by a combination of image and inference to make its compelling linkages.

HONORABLE MENTION: Molly Sturdevant

“Irises, in the order of Modus Tollens”

after Anne Carson, “Stillness, Corners, Chairs”

I

If Tule Elk, then balanced understory.

Overgrown however, the foliage crowds.

The ungulate is losing range.

The fawn feels the first layer weaken.

Therefore not Tule Elk.

Roots melt, uprooted minerals loosen,

lost conjunctions and elements

blow away, fall down the page.

A young woman on the news

stands where the fawn retreated.

She is clutching at her chest

trying to keep her organs inside

there we see it, the walls of her bedroom,

her personal corners, softening

in the mud now descending

where no cliff was.

II

If irises then, I walk out in the morning

with this purple being standing there

its purple head a queen

its yellow brains a thought.

I don’t go out this morning.

Therefore, not the iris.

III

Modus tollens is sad. The way of erasing

plays hard with time, unbuilds, ούκ, ἔςτι, undoes.

IV

If we cap carbon

then we live.

But say we do not.

This poem without countenance

smacks

of death

V

Theophrastus offers a remedy.

The only way to refute modus tollens

is to reclaim the antecedent

.

We imagine us again

(and what is an image but modus ponens)

we put ourselves back in

to an ordinary evening. We, existing,

skin made of nerves,

enjoy now, in this example a life

powered by sun, the hard panels

slant near our garden.

There we sit. Among the peppers

the raggedy hosta, the boxwood

never dies. Lawn chairs like copulas affirm

these hard, tall spears of fluted iris.

JUDGE’S COMMENT:

“Irises, in the order of Modus Tollens”

This poem yields its secrets once you look up Modus Tollens and discover that it is a mode of logical deductive argument. If P, then Q; if not Q, then not P. Tule Elk will exist if the marshland undergrowth that is their food exists. If no undergrowth, no elk. If you walk out in the morning and see the iris, the iris exists because you exist and see them. If you don’t walk out, no iris. The poem points up interrelationships that underlie continuation and basic existence. Our carbon footprint has consequences. The remedy is to “imagine us again” in a world where human constructions (house, lawn chairs) co-exist with sun and garden, with plants of various hardiness—and with iris. We have to see the world for ourselves for it to exist—that’s a first step. And if we don’t see it? This poem adds to its images of the natural world the implacability of logical deduction. Not an ordinary coupling in a poem, but a compelling pairing in this one, which links domestic environment with a natural environment, natural law to the laws of logic.

Winning Poems 2019 Connecticut River Review Contest

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

Contest Judge

Leslie McGrath is the author of three full-length poetry collections, Feminists Are Passing from Our Lives, Opulent Hunger, Opulent Rage, and Out from the Pleiades. Winner of the Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry and the Gretchen Warren award from the New England Poetry Club, her poems and interviews have been published in Agni, Poetry magazine, The Academy of American Poets, The Writer’s Chronicle, and The Yale Review. McGrath teaches creative writing at Central CT State University.

|

Winning Poems 2018 Connecticut River Review Contest

|

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

|

2018 Contest Judge Daniel Donaghy

Daniel Donaghy is a Professor of English at Eastern Connecticut State University. His books include SOMERSET (NYQ Books, 2018), Start with the Trouble (University of Arkansas Press, 2009), winner of the Paterson Award for Literary Excellence, and STREETFIGHTING (BkMk Press, 2005).

|

Winning Poems 2017 Connecticut River Review Contest

|

First Place

“Struck by Light,” by Lenore Hart 1 Each August raccoons the size of bluetick hounds run rabid here, a fanatical light in their eyes. It's not odd to see, at least once, a grizzled boar hog mad with the heat come trotting down your driveway, tusks first. That's when you don't pause. Just drop the grocery bags, grab the baby, and run like hell for the front door. In this flat land where spring water oozes up from submerged limestone caves, electricity grows wild on the thick damp air. Sometimes the hot hum congeals into a bright spear and falls, piercing the humidity, blasting a tree in the yard behind the house to shrapnel. 2 One night my aunt Ruth was at home reading to three little girls when a thunderstorm blew up off the shallow dish of lake. Light flashed in the rented pasture. She went outside carrying a lantern and found one cow dead on its back, outthrust legs stiff as rebar. Back inside she cursed, threw back a stiff whiskey and milk, then selected the sharpest butcher knife in the drawer. "You girls stay here. Don't look outside," she ordered. Naturally we all huddled at the window, and saw her slice the heifer's throat to bleed her dry. Flesh spoils fast in hot weather, which was the only kind we had. We knew pot roasts came from cows. And that, out in the country, nobody ever wastes good meat. 3 On the golf course, on the country-club side of the lake, a tourist was struck by the light. A single jolt fizzed his blood and made him see galaxies. The hot blow flung his five-iron into the pond so hard the splash startled the gators. Later they said the golfer's clothes were blown clean off, his spiked leather shoes burnt to jerky. The hole in his flat little cap you could put a fist clean through. His widow sold up their pretty white house and moved back to Boston, where electricity rides through wires, not on the air, and has the manners to stay decently out of sight, inside the papered walls. 4 In eighth grade a friend and I decided to walk into town. Six miles is a trip around the block when you're long-legged and thirteen. Telling no one, we set out down the red-clay lane. We'd only hiked halfway to the main road when dark clouds gathered overhead like the scowl of a tall, flouted parent. Three more steps and the sky ruptured, pouring water and pinging hail, turning the clay to gumbo. Drowned ship's rats, we crawled and clawed our way into the grove, huddling far from the trees. But light will not be mocked. It struck again, pulping the trunk of an old Valencia ten feet away. The side flash laid us out as if for early burial. We wallowed in the gritty soup, smeared with tears, clinging like monkeys, screaming each other deaf. 5 An hour or a day later (we could no longer fathom time) a passing electrician took pity. He stopped and bundled us, sodden, into his idling truck. "You girls must be in shock," he said kindly, sliding the shifter into gear. "Praise God you ain't all burnt up." Later in life I would discover the light had not entirely left my body. Even now the hands of a watch strapped on my wrist, no matter how costly, always click to a stop. But back then, perched on a sticky vinyl seat, picking greenwood splinters from my hair, staring out through a water-blind windshield, I understood for the first time that someday the light would be back. Every bit as sudden, with better aim, its burning spear unsheathed just for me. Judge: Ben Grossberg Statement: “Vivid and playful, “Struck By Light” reminds us that the novelist’s tools of character and scene belonged first to the poet. Yet the poem also takes on symbolic heft, as the speaker focuses in on her own close call and considers how lightning enlightens—by letting her glimpse her own mortality.” Honorable Mentions

“Piggyback Station” by David Prodell -for Tobias Engineer, conductor, single-passenger car, I’m the evening express departing the bottom stair, 8 pm-ish, with service to the south side second floor. My only fare grabs my shoulder, swings aboard, and clicks his hands around my neck. He chatters about how he outran a bumblebee, crafted an aircraft from popsicle sticks, drained a juice box in one gulp. We circle slowly through the lowlands-- living room, dining room, kitchen, family room. On the steep grade the piston “pop” in my right knee echoes in the darkened stairwell, and the freight of my day, software and hardware, seems heavier. Cheek on my shoulder, my traveler sleepily ticks off the banister rails passing like telephone poles until his daily news finally slips to the floor. The disembarkment to his bed doesn’t stir him so I sweep the aisles of his room and find in a blue jean’s pocket a dirty hunk of quartz from the playground. Come morning he’ll whisper his fingers open with a “Look, Daddy, see?” and tell me it’s a diamond for sure because once he cocoons something in his palm it always re-emerges transformed, magical, still warm with imagination. I’ll rest my shovel, turn the coal dust from my pockets, and with my son on my knee we’ll share the moment that has stopped me in my tracks: I too, will see a diamond. Judge: Ben Grossberg Statement: “Touching and richly detailed, “Piggyback Station” gracefully depicts the reciprocity of love. The father receives a flight of fancy from his son—entrance into his son’s imaginative world—just as the son receives a piggyback ride from his father.” ++++++++++++++++++++++++ Honorable Mention “Washing Strangers” by Micah Ruelle The first time it wasn’t romantic-- just part of my job. Also, the hair in odd places startled me because it was patchy, like a goat’s. My family visited the Iowa State Fair, & browsed the stockyards. Famers in boots used long hoses to wash the goats of flies & grime as if they were tractors or combines. & I don’t want to wash her like that-- still—my body is an animal’s: nails, hair, teeth, muscle, fat—all, like the one I’m about to wash. Baptism. That’s what it is. It won’t come to me till I begin massaging the shampoo out of her scalp. While rinsing, I’ll wonder if maybe the first baptism felt as awkward as this one, although nothing miraculous happens this time… except for maybe how stark & ghostly she looks—even against the white tile as she stared downward at the faucet. When she asked to dab her eyes, I moved the shower head & looked at the ceiling-- & realized that no one tells you when to look & when not to-- save for checking the hair in her pelvic area for soap to eliminate the risk of infection. So, I look-- a quick glance, & I feel a flush in my cheeks when I ask her to rinse again. But, I don’t want her to think that she is unbearable to look at, either like the first time I wore a two-piece to the lake & the boys neither noticed nor were mean to me as ache filled them while watching my older, bronzing cousins. They were kind enough to pass over me & through the summer, waiting to collect on the glances while my back was turned, not knowing to look. She says she wants to finish scrubbing on her own, I turn away. When she’s done rinsing, I turn off the faucet. Grab a towel. She sways into the clothed embrace like a newly birthed calf—sideways, & turns her back to me, & I secretly hope that it was interpreted as the closest to love as I could give, without looking. Judge: Ben Grossberg Statement: “No one tells you when to look/ & when not to—”: “Washing Strangers” looks, and looks steadily, at the forced intimacy of those whose jobs it is to care for people they do not know. This poem evokes the body in its decline with great compassion, never losing sight of its dignity or the rituals of privacy.” |

Second Place

“Says the Father to the Night from His Emptied Nest” by John Sibley Williams What it’s like to pitch half-drunk bottles at the dimming stars, ruin against ruin, all the season’s hay into a meadow-sized bundle for burning. The horses and the children are dead or moving on. It’s up to me to trample the field alone, to suicide by living here thirty more years, to craft an image of a barn to outlast these cinders. Some say the first body, made of dust, wept from its impotence over the world risen from its ribs. Some say there are still snakes under the porch speaking to us. Once I saw a carnage of blackbirds pecking straw from the head of a scarecrow wearing my shirt, and for a moment I saw myself again, beautiful in them. Judge: Ben Grossberg Statement: “Says a Father” is in equal measure psychological and sociological, documenting the decline of the family farm, a way of life. The emblems here are especially striking: half-drunk bottles, a meadow-sized bundle of hay, and finally “a carnage of blackbirds” pecking at a scarecrow made of the speaker’s clothes. A deft, inventive, and nearly apocalyptic poem.” Third Place

“Burning My Brother”

by Henry Hart New Year’s Day, I hauled the spruce decorated with tinsel to the compost heap where a jack o’ lantern glared from eye-pits. Sun had faded to a smoke stain on the cliff and apple trees by our barn. Ice thundered in the distant swamp. Grabbing the spruce’s top shoot, my brother drizzled a soup can of gas on needles. Drops splashed on his hands and blue jacket. Too dumb to know vapor explodes, I struck a match and jumped when the whole tree whooshed into flame. Even now I see my brother plunge into snow and stumble toward me, red hands steaming like lobster claws in the frigid air. Judge: Ben Grossberg Statement: “This haunted elegy moves with great precision to its piercing conclusion, a memory of the brother “stumbl[ing] toward me, red hands/ steaming like lobster claws in the frigid air.” “Even now,” the poet writes, “I see my brother.” We see him, too—incandescent, stricken—as he lurches forward, simultaneously out of the past and the grave.” |