Margaret Gibson Poet Laureate Contest 2023 Winners

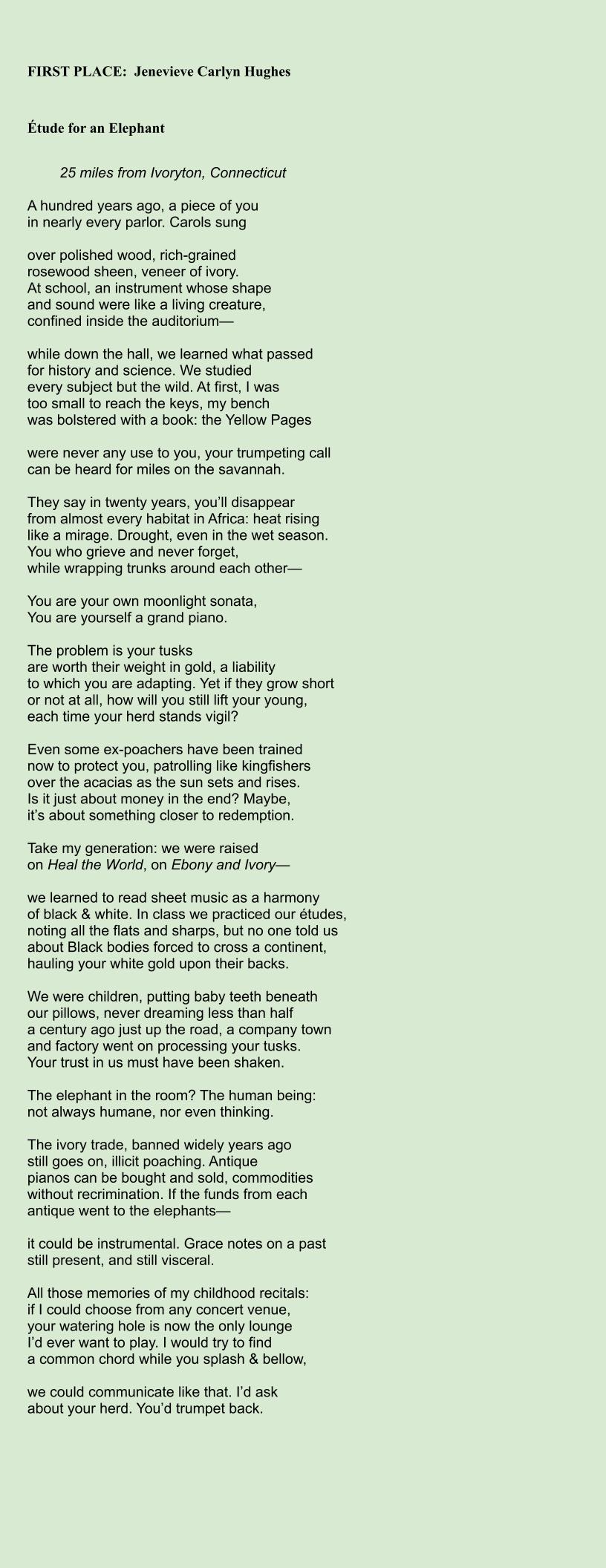

First Place Winner: Jenevieve Carlyn Hughes

Judge’s Remarks:

With an engaging, reflective voice that moves easily from personal memory to facts about history, science, commerce and slave trade, “Etude for Elephant” explores the exploitation of elephants for their ivory tusks and their possible extinction—if poaching and drought from climate change continue. As her metaphors unfold, the poem is able to link ivory traffic and piano recital, elephant and piano, Ivoryton and Africa, creating a binding force that unifies and makes inference potent. By turns serious and playful, this poem looks for “the common chord,” that is, a way to transform exploitation to engagement and survival. Deftly the poem reveals that music, and by extension all of the arts, are supported by exploitation—both of elephants and of human beings. And yet the poet offers the hope of reparation, of change, of art that takes responsibility for engagement with environmental injustice. At the close of the poem, the poet (at one time a childhood pianist) imagines a “concert venue” for herself—the elephant’s watering hole. “I would try to find/ a common chord while you splash and bellow . . . I’d ask about your herd. You’d trumpet back.” From Ivoryton in CT to Africa, from ignorance to understanding, from separation to closer relationship, this poem weaves its patterns. It is a lament, a praise poem, and a teaching.

With an engaging, reflective voice that moves easily from personal memory to facts about history, science, commerce and slave trade, “Etude for Elephant” explores the exploitation of elephants for their ivory tusks and their possible extinction—if poaching and drought from climate change continue. As her metaphors unfold, the poem is able to link ivory traffic and piano recital, elephant and piano, Ivoryton and Africa, creating a binding force that unifies and makes inference potent. By turns serious and playful, this poem looks for “the common chord,” that is, a way to transform exploitation to engagement and survival. Deftly the poem reveals that music, and by extension all of the arts, are supported by exploitation—both of elephants and of human beings. And yet the poet offers the hope of reparation, of change, of art that takes responsibility for engagement with environmental injustice. At the close of the poem, the poet (at one time a childhood pianist) imagines a “concert venue” for herself—the elephant’s watering hole. “I would try to find/ a common chord while you splash and bellow . . . I’d ask about your herd. You’d trumpet back.” From Ivoryton in CT to Africa, from ignorance to understanding, from separation to closer relationship, this poem weaves its patterns. It is a lament, a praise poem, and a teaching.

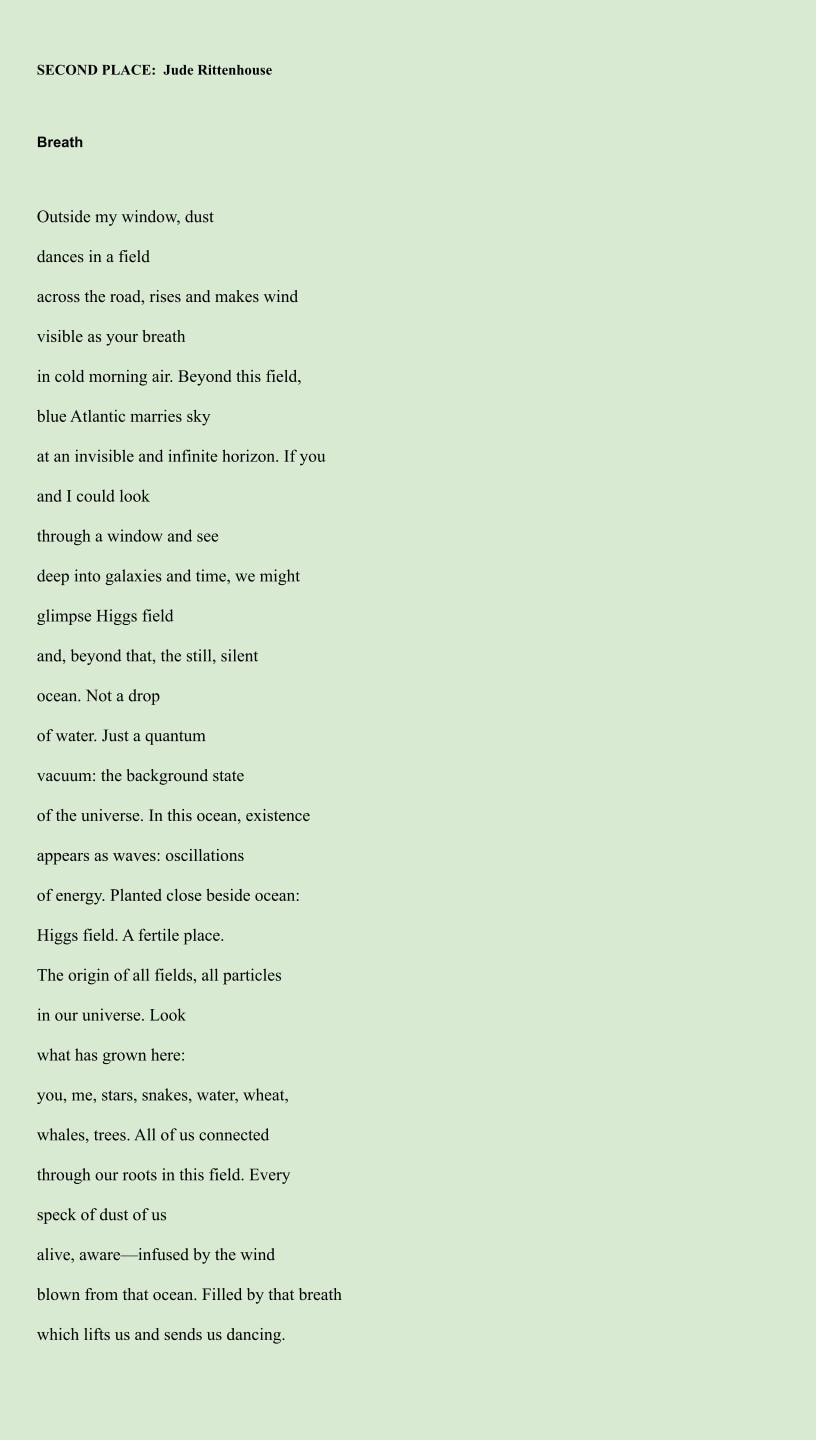

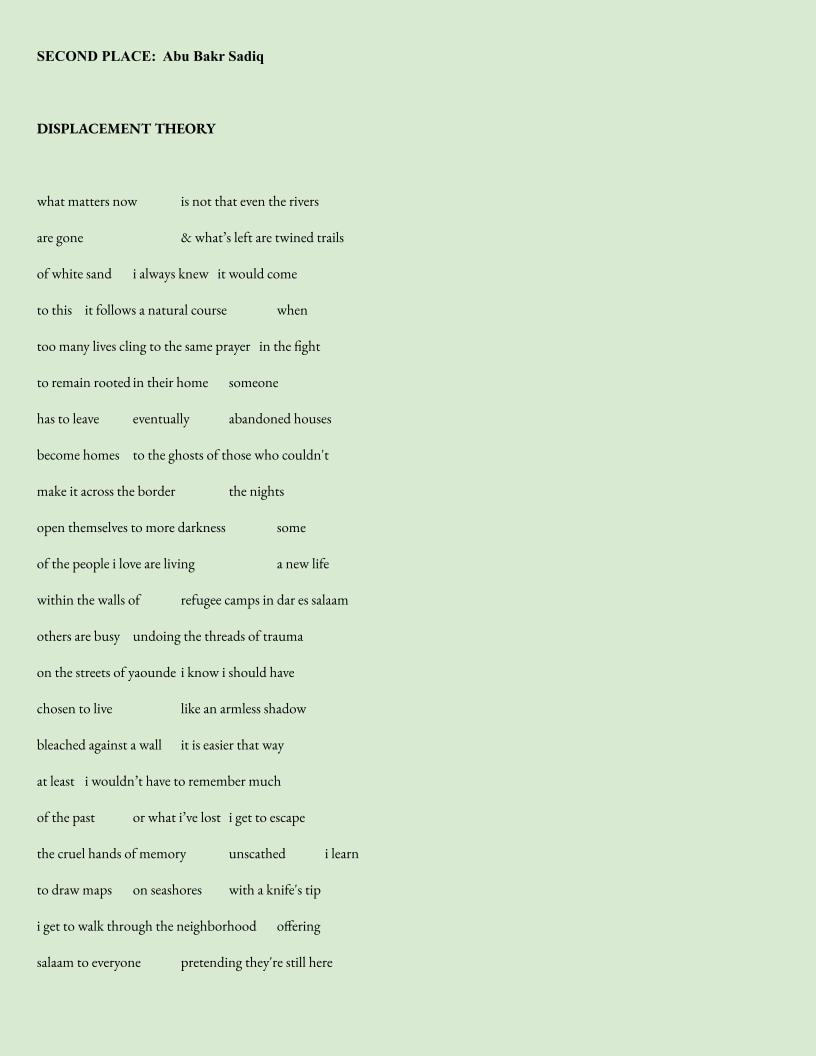

Second Place Winners: Jude Rittenhouse and Abu Bakr Sadiq

Judge’s Remarks:

What a powerful articulation of the connectedness of all things! Moving from the field outside her window, where dust rises and “makes wind/visible as your breath/in cold morning air,” and where “blue Atlantic marries sky,” the poet makes a giant step into galaxies and time, into the Higgs field and the oceanic background quantum state of the universe. In this “fertile” field, we look and find what has “grown here.” Merely everything on our plane of existence that appears, separate. But no: in the Higgs field there is , “Every/speck of dust of us/alive, aware.” I love the calm clarity of voice, the careful linking of what is visible to us as humans and that which is not. This poem lays a foundation in science for a way of seeing our connectedness that (by implication) just might lift us into a different way of living and being in the world. This poem offers new ground to stand on.

What a powerful articulation of the connectedness of all things! Moving from the field outside her window, where dust rises and “makes wind/visible as your breath/in cold morning air,” and where “blue Atlantic marries sky,” the poet makes a giant step into galaxies and time, into the Higgs field and the oceanic background quantum state of the universe. In this “fertile” field, we look and find what has “grown here.” Merely everything on our plane of existence that appears, separate. But no: in the Higgs field there is , “Every/speck of dust of us/alive, aware.” I love the calm clarity of voice, the careful linking of what is visible to us as humans and that which is not. This poem lays a foundation in science for a way of seeing our connectedness that (by implication) just might lift us into a different way of living and being in the world. This poem offers new ground to stand on.

Judge’s Remarks:

Reading this poem aloud, one can experience the spaces left within the lines as a way to slow down and pay attention; we’re forced to breath, to pause when we might otherwise read more quickly—we gasp for air, we begin to feel the grief and pain of the speaker viscerally. In this poem, “the rivers are gone;” also gone from this land of sand are the human beings who lived there with their families, and in their homes. Displaced by drought and a forced migration, the speaker lives her new life in a refugee camp, wishing that she were “a shadow/bleached against a wall.” Better that death than this life with ghosts, “offering/salaam to everyone pretending they’re still here.” Here is a poem that enacts grief through language and passes it from her mind and body to ours. The music of this poem is a broken one, but through its dissonance the reader is made to pay attention to the human consequences of global climate disaster in a new and more visceral way.

Reading this poem aloud, one can experience the spaces left within the lines as a way to slow down and pay attention; we’re forced to breath, to pause when we might otherwise read more quickly—we gasp for air, we begin to feel the grief and pain of the speaker viscerally. In this poem, “the rivers are gone;” also gone from this land of sand are the human beings who lived there with their families, and in their homes. Displaced by drought and a forced migration, the speaker lives her new life in a refugee camp, wishing that she were “a shadow/bleached against a wall.” Better that death than this life with ghosts, “offering/salaam to everyone pretending they’re still here.” Here is a poem that enacts grief through language and passes it from her mind and body to ours. The music of this poem is a broken one, but through its dissonance the reader is made to pay attention to the human consequences of global climate disaster in a new and more visceral way.

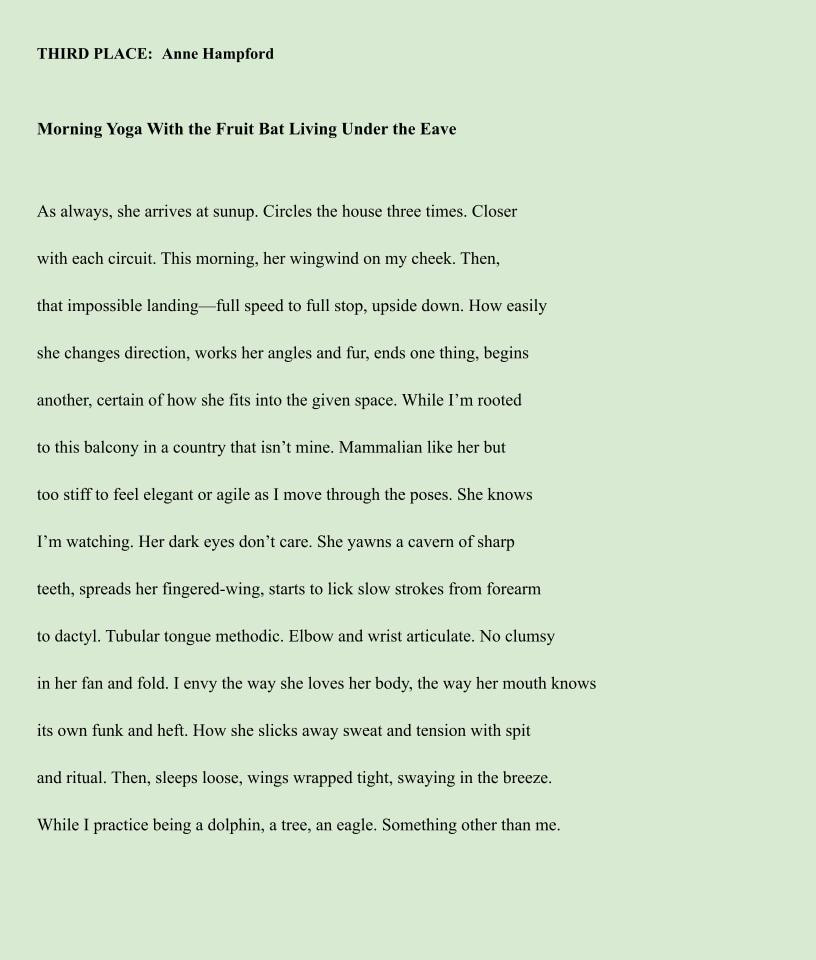

Third Place: Anne Hampford

Judge’s Remarks:

Such a delight this poem is! I confess I’m a sucker for close attention to the movement and behaviors of the “other”, in this case a fruit bat closely observed during the speaker’s morning yoga time. I love the speaker’s careful attention, how it shifts into praise, how it shifts into contrast with the speaker’s own awareness of her body’s lack of agility. Oh, but this speaker’s mind is agile, and the voice of the poem is as well. How well wrought are these long lines that, like the fruit bat, “come closer with each circuit.” The poem is a celebration of “the way she loves her body” (the fruit bat) and how by contrast the speaker is trying to be everything she is not. She suggests this by naming the asanas: dolphin, tree, eagle. Something other than me.” The poem is a deft complaint about human alienation, and a praise poem to the fruit bat. Since the root of the word yoga is “to yoke” it also offers hope for our learning how to be with ourselves and others, how to affirm, how to live in a respectful way with ourselves and others

Such a delight this poem is! I confess I’m a sucker for close attention to the movement and behaviors of the “other”, in this case a fruit bat closely observed during the speaker’s morning yoga time. I love the speaker’s careful attention, how it shifts into praise, how it shifts into contrast with the speaker’s own awareness of her body’s lack of agility. Oh, but this speaker’s mind is agile, and the voice of the poem is as well. How well wrought are these long lines that, like the fruit bat, “come closer with each circuit.” The poem is a celebration of “the way she loves her body” (the fruit bat) and how by contrast the speaker is trying to be everything she is not. She suggests this by naming the asanas: dolphin, tree, eagle. Something other than me.” The poem is a deft complaint about human alienation, and a praise poem to the fruit bat. Since the root of the word yoga is “to yoke” it also offers hope for our learning how to be with ourselves and others, how to affirm, how to live in a respectful way with ourselves and others

HONORABLE MENTIONS:

Jeanine DeRusha, “Albatross”; David Epstein, “Fuimus Poetica”

Jeanine DeRusha, “Albatross”; David Epstein, “Fuimus Poetica”